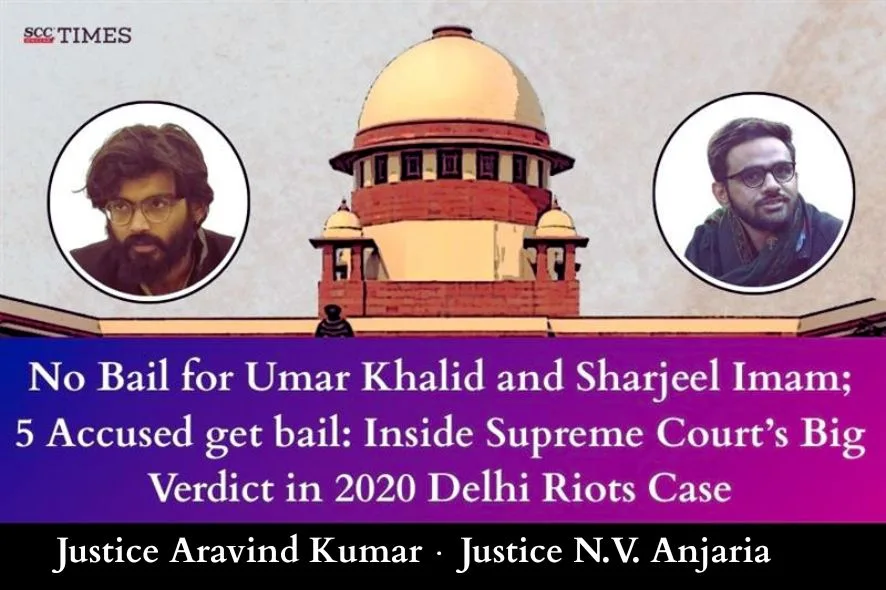

Supreme Court: While considering the bail pleas of Sharjeel Imam, Umar Khalid, Shifa Ur Rehman, Mohd. Saleem Khan, Meeran Haider, Shadab Ahmed and Gulfisha Fatima who were booked under several provisions of Penal Code, 1860, Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), Arms Act and Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act, 1984, for their alleged involvement in 2020 Delhi NCR communal riots and larger conspiracy; the Division Bench of Aravind Kumar* and N.V. Anjaria, JJ., refused to grant bail to Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid, expressing satisfaction that the prosecution material prima facie discloses attribution of a central and formative role by the 2 accused persons.

Vis-a-vis Shifa Ur Rehman, Mohd. Saleem Khan, Meeran Haider, Shadab Ahmed and Gulfisha Fatima, the Court decided to grant them conditional bail having regard to the role attributed, the nature of the material relied upon, and the present stage of the proceedings.

Background:

In February 2020, Delhi NCR was gripped by violence and communal tensions owing to riots, which subsequently led to registration of FIR. The prosecution alleged a pre-planned criminal conspiracy involving several accused persons, including the 7 appellants (accused persons). It was alleged that the conspiracy was hatched with the object of orchestrating riots in the National Capital Territory of Delhi as a form of protest against the enactment of the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) and the proposed National Register of Citizens (NRC). It was further alleged that the conspiracy culminated in the deliberate incitement of widespread communal violence on and around 22nd, 23rd, and 24th February 2020. The acts allegedly committed during this period were not spontaneous but were the outcome of coordinated efforts to inflame tensions, mobilise crowds and execute violent actions across various parts of Delhi. The riots resulted in grave consequences, including the loss of 54 lives, among them a senior police officer and an Intelligence Bureau official, as well as grievous injuries to several police personnel and civilians. In addition, extensive damage was caused to over 1,500 public and private properties, alongside substantial intangible harm to public order, social harmony, and the nation at large.

Consequently, the accused persons were apprehended, investigations began and upon completion of investigation, a chargesheet came to be filed alleging offences under Sections 120B read with Sections 109, 114, 124-A, 147, 148, 149, 153-A, 186, 201, 212, 295, 302, 307, 341, 353, 395, 420, 427, 435, 436, 452, 454, 468, 471 and 34 of the IPC; Sections 13, 16, 17 and 18 of the UAPA, 1967; Sections 25 and 27 of the Arms Act and Sections 3 and 4 of the Prevention of Damage to Public Property Act, 1984.

Court’s Assessment:

Perusing the case, the Court made its assessment under the following heads:

Prolonged incarceration and plea under Article 21

The Court noted the accused persons’ plea regarding prolonged incarceration, coupled with the absence of any realistic prospect of early conclusion of trial, which rendered continued detention constitutionally impermissible. The Court clarified that under the contours of UAPA, the plea of delay engages Article 21 at two distinct constitutional planes. First, delay may be of such magnitude that continued detention becomes per se unconstitutional, irrespective of the strength of the prosecution case. Second, delay may be pressed as a circumstance to contend that the statutory satisfaction under Section 43D(5) stands diluted or displaced. The present case, on an examination of the record, does not meet either threshold. The Court explained that the constitutional inquiry into delay is not an inquiry into guilt. It is an inquiry into whether continued detention remains constitutionally permissible in the circumstances of the case. That inquiry is necessarily contextual. The Court further pointed out that it is conscious that the accused persons in the present appeal may not stand on identical factual footing in all respects with the co-accused whose appeal was considered by the High Court.

Noting cumulatively, the Court observed that the record did not support the absolute proposition that the accused persons have remained “innocently incarcerated” without any contribution to delay, nor does it disclose a situation where the delay is so wholly unjustified as to override the statutory embargo contained in Section 43D(5). The plea of delay in the facts of the particular case, therefore, does not warrant enlargement on bail, though it justifies continued judicial emphasis on the timely conduct of the proceedings.

Framework of Section 43D(5) UAPA and scope of judicial enquiry at bail stage

The Court explained that the expression “prima facie true”, which lies at the heart of Section 43D(5), does not invite a detailed examination of evidence, nor does it require the Court to assess the probability of conviction. Equally, it does not reduce the judicial role to a mechanical acceptance of the prosecution’s assertions. The statutory standard contemplates a threshold inquiry of limited but real content. The discipline imposed by Section 43D(5) necessarily circumscribes the nature of judicial scrutiny permissible at the bail stage. Any exercise approximating a mini-trial at this stage would transgress the statutory boundary deliberately drawn by Parliament. The Court enumerated the enquiries that should be undertaken for Section 43D(5).

Scope of “terrorist act” under Section 15 UAPA and statutory context

The Court explained that the prima facie satisfaction contemplated by Section 43D(5) is not a matter of impression or gravity alone; it is a satisfaction referable to defined statutory ingredients. Section 15 of the Act defines what constitutes a “terrorist act” for the purposes of the statute. The definition is structured around two essential elements. First, the act must be done with intent to threaten, or be likely to threaten, the unity, integrity, security, including economic security, or sovereignty of India, or with intent to strike terror in the people or any section thereof. Second, the act must be of such a nature as to cause, or be likely to cause, the consequences enumerated in the provision. “To construe Section 15 as limited only to conventional modes of violence would be to unduly narrow the provision, contrary to its plain language”. Furthermore, read together, Sections 15 and 18 disclose a legislative design wherein Section 15 defines the nature of acts which Parliament has characterised as terrorist acts, while Section 18 ensures that criminal liability is not confined only to the final execution, but extends to those who contribute to the commission of such acts through planning, coordination, mobilisation, or other forms of concerted action.

Individualised role and differentiation in treatment of the prime conspirators with others

The Court observed that the record disclosed that all the accused persons do not stand on an equal footing as regards culpability. The allegations against the principal accused indicate a central and directive role in conceptualising, planning, and coordinating the alleged terrorist act, whereas the material against certain co-accused reflects conduct of a subsidiary or facilitative nature. The hierarchy of participation, emerging from the prosecution’s case itself, requires the Court to assess each application individually, rather than proceed on the premise of equivalence. Such differentiation is intrinsic to criminal adjudication and operates irrespective of the uniformity of charges framed.

The Court noted that against Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, the prosecution material comprises direct, corroborative, and contemporaneous evidence, including recoveries, digital communication trails, and statements indicative of managerial responsibility. In contrast, the involvement of others is sought to be established mainly through associative or peripheral conduct. The Court cannot ignore that where evidentiary strength varies materially between accused persons, the need for continued detention likewise varies. The Court further observed that a cumulative and comparative reading of the FIR and the successive charge-sheets disclosed a discernible differentiation in the nature, scope, and hierarchy of roles attributed to the accused persons. This structural distinction cannot be ignored and must inform any judicial determination relating to culpability, parity, or the applicability of penal provisions requiring a heightened threshold of intent and participation. “Having thus delineated the structural and evidentiary differentiation emerging from the prosecution case itself, it becomes necessary for the Court to examine the bail pleas in an accused-specific manner. The exercise that follows is not one of adjudicating culpability, which lies exclusively within the domain of trial, but of assessing whether the statutory threshold governing pre-trial liberty is attracted qua each appellant”.

Thereafter, the Court proceeded to consider the submissions made by the 7 accused persons, the respondents and findings made by the Trial Court and Delhi High Court.

Conclusion and Operative Directions:

“When bail is sought in prosecutions governed by a special statute, the Court is required to undertake a difficult and sensitive balancing exercise, conscious that neither liberty nor security admits of absolutism”.

Accused Persons who were Denied Bail

Declining bail to Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid, the Court stated that the material suggests involvement at the level of planning, mobilisation, and strategic direction, extending beyond episodic or localised acts. The statutory threshold under Section 43D (5) of the UAPA, therefore stands attracted qua these appellants. The Court opined that it was not persuaded that, on the present record, continued detention has crossed the threshold of constitutional impermissibility so as to override the statutory embargo. The complexity of the prosecution, the nature of evidence relied upon, and the stage of the proceedings do not justify their enlargement on bail at this juncture. Hence, their appeals were rejected.

The Court further opined that on the completion of the examination of the protected witnesses relied upon by the prosecution, or upon the expiry of a period of one year from the date of this order, whichever is earlier, these two accused persons would be at liberty to renew their prayer for grant of bail before the jurisdictional Court.

Accused Persons who were Granted Conditional Bail

The Court allowed the appeals of the remaining 5 accused persons and emphasised that the grant of bail in their favour does not reflect any dilution of the seriousness of the allegations, nor does it amount to a finding on guilt. It represents a calibrated exercise of constitutional discretion, structured to preserve both liberty of the individual and security of the nation.

The Court directed their release subject to certain conditions including executing a personal bond in the sum of ₹2,00,000 with two local sureties of the like sum to the satisfaction of the Trial Court.

Concluding Remarks:

The Constitution guarantees personal liberty, but it does not conceive liberty as an isolated or absolute entitlement, detached from the security of the society in which it operates. Where a special statutory framework has been enacted to address offences perceived to strike at these foundations, courts are duty-bound to give effect to that framework, subject always to constitutional discipline. Those alleged to have conceived, directed, or steered unlawful activity or terrorist activity stand on a different legal footing from those whose alleged involvement is confined to facilitation or participation at a different level. To disregard such distinctions would itself result in arbitrariness.

The Court clarified that it has not examined the merits of the prosecution case beyond the confines mandated at the stage of consideration of an application seeking bail, nor has it expressed any opinion on the ultimate culpability of any of the accused. All observations are confined to the material presently on record and to the statutory and constitutional standards governing pre-trial liberty under a special enactment.

Having regard to the nature of the prosecution and the period of incarceration already undergone, the Court directed that the Trial Court shall proceed with the matter with due expedition and shall endeavour to ensure that the examination of witnesses, particularly the protected witnesses relied upon by the prosecution, is taken up and carried forward without delay. Prosecution shall take all necessary steps to secure the presence of its witnesses on the dates fixed and the parties shall refrain from seeking adjournments except for reasons which are unavoidable. The Trial Court shall be at liberty to regulate the proceedings in accordance with law so as to ensure that the trial is not unnecessarily prolonged, while at the same time safeguarding the rights of all parties.

[Gulfisha Fatima v. State (Govt. of NCT Delhi), 2026 SCC OnLine SC 10, decided on 5-1-2026]

*Judgment by Justice Aravind Kumar

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For Petitioner(s): Mr. Siddharth Luthra, Sr. Adv. Mr. Kartik Murukutla, Sr. Adv. Mr. Farrukh Rasheed, AOR Mr. Shivam Sharma, Adv. Ms. Deeksha Dwivedi, Adv. Mr. Rahul Dev, Adv. Ms. Shifa, Adv. Mr. Gautam Khazanchi, Adv. Mr. Vaibhav Dubey, Adv. Mr. Bilal Mansoor, Adv. Ms. Aishwarya Singh, Adv. Ms. Pooja Deepak, Adv. Ms. Anshala Verma, Adv. Mr. Mansoor Ali, AOR Mr. Shivansh Sharma, Adv. Ms. Rubina Jawed, Adv. Ms. Saima Jawed, Adv. Mr. Salman Khurshid, Sr. Adv. Mr. Bilal Anwar Khan, Adv. Ms. Anshu Kapoor, Adv. Ms. Sidra Khan, Adv. Ms. Mariya Mansuri, Adv. Mr. Varun Bhati, Adv. Mr. Ankit Singh, Adv. Mr. Shashank Singh, AOR Mr. Kapil Sibal, Sr. Adv. Mr. C. U. Singh, Sr. Adv. Mr. Trideep Pais, Sr. Adv. Ms. Sanya Kumar, Adv. Mr. Sahil Ghai, Adv. Mr. N. Sai Vinod, AOR Ms. Aparajita Jamwal, Adv. Mr. Nikhil Pahwa, Adv. Ms. Saloni Ambastha, Adv. Ms. Sakshi Jain, Adv. Mr. Abhik Chimni, Adv. Ms. Bidya Mohanty, Adv. Ms. Katyayani Suhrud, Adv. Mr. Abhishek Kalaiyarsan, Adv. Mr. Aekansh Agarwal, Adv. Ms. Kanu Garg, Adv. Mr. Siddharth Aggarwal, Sr. Adv. Mr. Shri Singh, Adv. Mr. Faraz Maqbool, Adv. Mr. Kumar Vaibhaw, Adv. Ms. Sana Juneja, Adv. Ms. A. Sahitya Veena, Adv. Ms. Deepshikha, Adv. Ms. Arunima Nair, Adv. Mr. Vismita Diwan, Adv. Ms. Arshiya Ghosh, Adv. Mr. Sidhant Saraswat, Adv. Ms. Somaya Gupta, Adv. Ms. Devina Sehgal, AOR Ms. Chinmayi Chatterjee, Adv. Ms. Swati Khanna, Adv. Dr. Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Sr. Adv. Mr. Sarim Naved, Adv. Mr. Harsh Bora, Adv. Ms. Maulshree Pathak, AOR Mr. Shahid Nadeem, Adv. Mr. Amit Bhandari, Adv. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan, Adv. Mr. Omar Hoda, Adv. Ms. Eesha Bakshi, Adv. Ms. Namrah Nasir, Adv. Mr. Uday Bhatia, Adv. Mr. Siddharth Srivastava, Adv. Mr. Surya Kiran, Adv. Mr. Siddhartha Dave, Sr. Adv. Ms. Fauzia Shakil, AOR Mr. Talib Mustafa, Adv. Mr. Ahmad Ibrahim, Adv. Ms. Tasmiya Taleha, Adv. Ms. Alekhya Shastry, Adv. Ms. Raksha Agrawal, Adv. Ms. Ayesha Zaidi, Adv. Mr. Abhishek Singh, Adv. Mr. Kartik Venu, Adv. Mr. Jeet Chakrabarti, Adv. Mr. Sourav Verma, Adv.

For Respondent(s): Mr. Suryaprakash V. Raju, ASG Mr. Mukesh Kumar Maroria, AOR