Legislative enactments should preserve the pyramidal model of adjudication where most of the litigation attains its finality at the District Court.

A cursory glance at the legislations, brought over the last 3-4 decades will reflect our ingenuity and consummate skill in devising means, methods and procedure to increase pendency and delay in the adjudicatory process. We have mastered this to a level of art, so much so that every such new legislation comes with a prospect of contributing to the malady, rather than becoming a remedy. Special Acts are brought with enhanced penal provisions and Special Courts are constituted for speedy disposal of cases. Most of these Special Courts are presided over by judicial officers in the rank of District Judges to adjudicate cases of specific nature. On paper, this appears to be a good move to expedite the adjudicatory process of a specific type of litigation. In their actual working the object of speedy justice has been belied and to a large extent they have proved to be counterproductive.

While the new Acts provides for creation of Special Courts, they do not necessarily lead to sanction of new posts and infrastructure, rather, already functional courts are designated as Special Courts and the pending cases of the type are transferred to the Special Courts. This leads to the concentration of a particular type of cases in such courts, which were previously pending before different courts, burdening them with cases far beyond their capacity, leading to further delay in disposal of the cases. Ironically, this frustrates the object with which such Special Courts are established.

It is not only the trial of cases that gets impeded, but it also has an adverse impact on the appeals and revisions. Special Courts are constituted with District Judges as their Presiding Officers. Resultantly, the cases including the appeals from interim or final order which were earlier concluded at the District Court level, now travel to the High Courts creating not only additional hardships for the litigants but also increasing the pendency of cases at the High Court level. A few instances of such legislation shall bear out the point being made here.

Family Courts

The Family Courts Act, enacted in 1984, sought to establish exclusive Family Courts, presided over by a Judge in the rank of District Judge, for the adjudication of matrimonial disputes; the jurisdiction of it has been defined in Section 2(d) of the Act. Section 8 of the Act ousted the jurisdiction of the District Courts and other subordinate civil courts and also of the Magisterial Courts in matters referred to in Section 2(d) of the Act. This included the cases arising out of applications related to maintenance under Section 125 or Section 127, Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) which were earlier adjudicated by Judicial Magistrates.

Before the Family Courts Act, the matrimonial suits were heard by the Courts of Munsifs and Sub-Judges, and the maintenance cases were heard by the Judicial Magistrates and appeals and revisions from the decrees and orders passed in these cases were maintainable before the District and Sessions Judge. The orders related to maintenance passed by a Family Court under Section 125 or Section 127 CrPC were revisable before the Sessions Judge and judgment and decree from matrimonial suits were appealable before the District Judge. Practically, litigations almost concluded at the District Courts level.

Now after the coming of the Family Courts Act, since the Family Judges are officers in the rank of District Judges, therefore forum of appeal and revision is only before the High Court. The impact of this legislation is that disputes before the Family Court do not attain finality at the District Court level, but it lingers on in appeal or revision before the High Court. From the judgment and decree passed by the District Judge in the first appeal, only the second appeal was maintainable on a substantial question of law before the High Court. Similarly, on disposal of revision by the District Judges against the order passed in maintenance cases by the Judicial Magistrates, only writ petition was maintainable for the High Court. Hearing in revision and second appeal are confined to the question of law, and substantial question of law respectively.

The Family Courts Act, has ushered in change of jurisdiction where each and every order passed by the Family Courts can be impugned only before the High Court, and it has been made a court of fact.

Before the Family Courts Act came into force, if there were 300 maintenance cases under Section 125 CrPC pending in a district, they were evenly distributed in the courts of different Judicial Magistrates and were not concentrated in one court. The District Judges used to monitor their progress in the monthly meeting and the distribution of these cases amongst different courts was the prerogative of the Principal District Judge who had the leeway of taking into consideration several factors, to ensure speedy and effective disposal of the cases. This included the individual aptitude and disposition of the respective officer. Result was expeditious disposal of maintenance cases by the Court of Magistrates and the litigation virtually ended in revision before the District Judges. Similarly, if there were hundred matrimonial suits of different nature in a district, they were distributed in the Court of Sub-Judges and the judgment and decree were appealable before the District Judge. This was a system where civil and criminal cases arising out of family disputes were disposed of at the district level and only few cases would traverse to the High Court.

An important aspect, probably overlooked by the legislature, was the very nature of maintenance litigation which remain active even after their final disposal. Fresh applications are filed for compliance of maintenance order in the same case, even after the final order is passed, if the order is not complied with. In case of default, the party has an option to move the Court, for every breach of the order. In order to enforce the compliance of the maintenance order, a warrant can be issued for levying the amount, and the Court may also sentence the accused to imprisonment for default under Section 125(3) CrPC.

Under Section 127 CrPC in the event of change of circumstances of any person, the maintenance amount can also be altered. There are petitions almost in each case to enforce the order of maintenance or for altering the maintenance amount by the trial court. These execution or alteration applications of the maintenance amount can be filed in the same court.

Fall out of the Family Courts Act is that all cases, i.e. maintenance and matrimonial, guardianship cases, have now been funnelled to one Family Court or, in larger districts, to other additional Family Courts. Concentration of all cases in one or two Family Courts entails heavy pendency in these courts. Speed of final disposal of such cases can be anyone’s guess, particularly when every decree and order is amenable to challenge before the High Court.

Spike in High Court pendency

Those aggrieved by the orders passed in maintenance cases, have no option but to approach the High Courts. Thus, the High Court gets inundated with appeals and revisions which were earlier disposed of at the District Courts level. The provision that judgments and orders passed in matrimonial suits can be disposed of only by Division Benches, as per Section 19 of the Family Courts Act, retards the prospect of their early disposal since the High Courts at their present strength can have only limited number of Division Benches for hearing diverse nature of cases. It is not logically and practically feasible to dispose of hundreds and thousands of such appeals and revisions arising from the different Family Courts spread out across in their respective State, within a reasonable span of time.

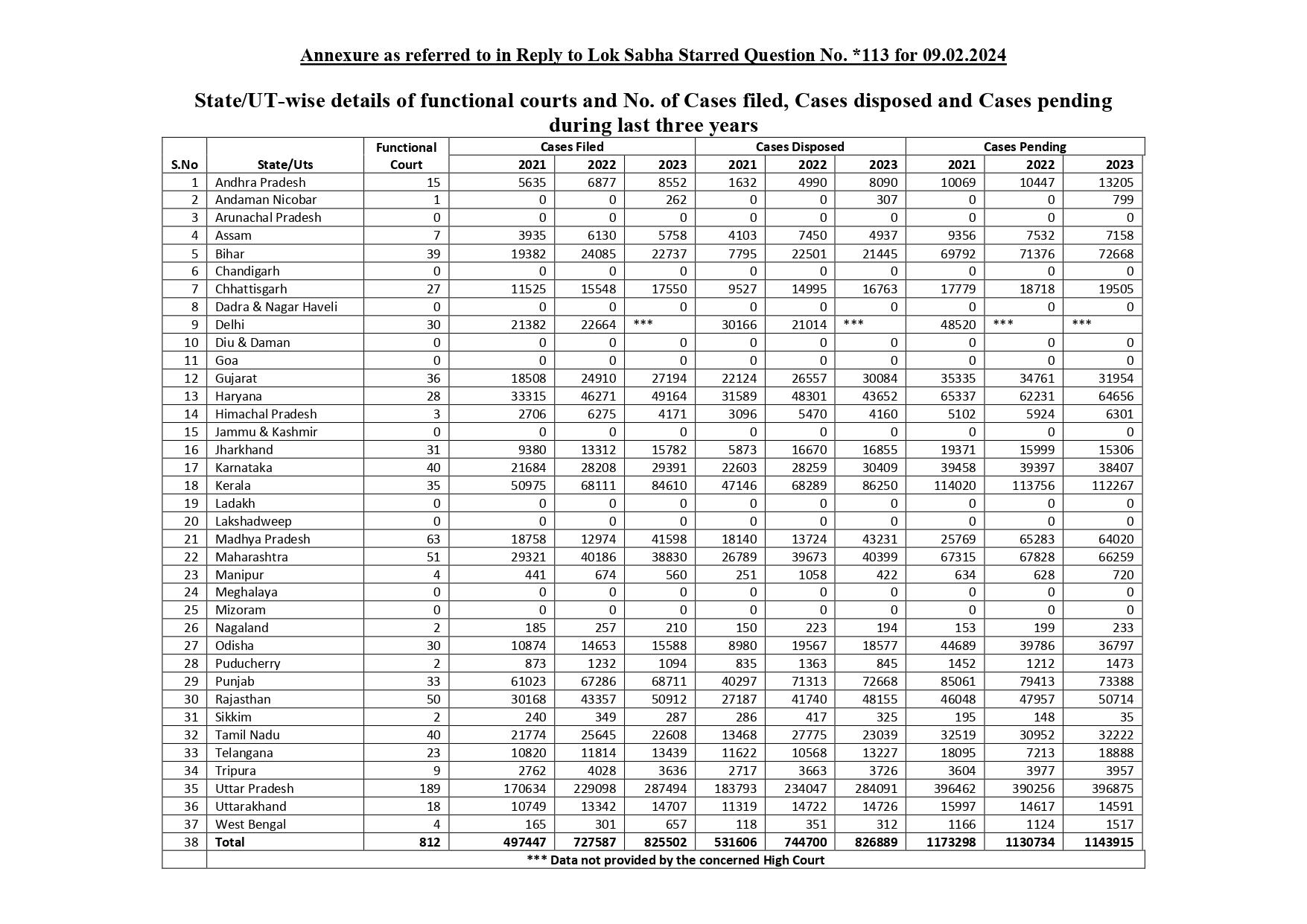

Today’s disposal of cases by the Family Courts, are tomorrow’s pendency before the High Court in appeal and revision. Pendency and disposal of cases of the Family Courts will fairly indicate the prospective appeals and revisions that may be flooding in the High Courts. Starred Question No. 1131 in the Lok Sabha was answered on 9-2-2024 with regard to the number of Family Courts (State-wise) functioning in the country and the number of pending cases in them. Extract of the pendency figure before these courts pan India is as under:

The above figures show disposal of more than eight lakh cases by the Family Courts in India in 2023 (excluding figures from some of the States), part of which are prospective appeals and revisions before the High Courts.

Management of judicial resources

The rationale underpinning the decision of the Government to establish Family Courts in every district of the country is hard to comprehend. There is a wide variation of pendency figures in each district depending upon their demography, urbanisation and level of education. The decision to have Family Courts in each district appears to have been conceived on the basis of the pendency figures in the metropolitan cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai and Bengaluru. India is not what these metros look like. It is bewildering to note that Family Courts presided over by a judicial officer of the rank of District Judge have been established in several small districts across the country which have abysmally low pendency figures. A brief glance at the pendency figure of cases in the Family Courts in Jharkhand2 will give a fair idea of the abovenoted incoherent and unsystematic set-up.

|

Sl. No. |

District |

Court-wise pendency |

|

1. |

Bokaro |

1491 |

|

2. |

Chaibasa |

31 |

|

3. |

Chatra |

107 |

|

4. |

Daltonganj |

734 |

|

5. |

Deoghar |

772 |

|

6. |

Dhanbad |

2154 |

|

7. |

Dumka |

350 |

|

8. |

Garhwa |

492 |

|

9. |

Giridih |

1518 |

|

10. |

Godda |

783 |

|

11. |

Gumla |

197 |

|

12. |

Hazaribag |

485 |

|

13. |

Jamshedpur |

2344 |

|

14. |

Jamtara |

217 |

|

15. |

Khunti |

31 |

|

16. |

Koderma |

278 |

|

17. |

Latehar |

90 |

|

18. |

Lohardaga |

70 |

|

19. |

Pakur |

211 |

|

20. |

Ramgarh |

478 |

|

21. |

Ranchi |

1968 |

|

22. |

Sahebganj |

664 |

|

23. |

Seraikela Kharsawan |

303 |

|

24. |

Simdega |

44 |

|

Total |

15809 |

(Pendency figures as on July 2024)

There is no Family Court functional at Khunti at present, and the power of Family Judge is vested in the Principal District Judge. The pendency of cases ranges from a few cases of about 31 in Chaibasa to 2344 in Jamshedpur in one Family Court. In larger districts with high pendency, more than one Family Courts are functional. It would not be an exaggeration to state that it is a gross misuse, to underutilise the judicial resources and the Court hours devoted by senior judicial officers by posting them as Principal Judge of Family Courts with ridiculously low pendency figures, compared to other courts. This sample study of Jharkhand gives an insight into the result of imposing a model of judicial adjudication from the top without factoring the local needs. The pattern is not unique to this State but with some variations is indicative of the state of affairs in other States as well.

There could have been some justification in the creation of Family Courts in large districts having a substantial number of pending cases, but the setting up of Family Courts in districts with low pendency figures, especially when most of the cases are related to maintenance under Section 125 CrPC, is beyond comprehension.

The result is that family disputes are not being resolved at the district level and is increasing the pendency in the High Court level on its appellate and revisional side. The Family Courts Act, instead of providing succour to the families singing in these litigations, have set-up process and procedure which has resulted in exacerbating the problem. Litigation arising out of family disputes have cascading effect as they give rise to multiple litigations, both civil and criminal which may be for domestic violence under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, cruelty under Section 498-A, and for guardianship of child and counter-cases under Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). Delay in disposal of family cases have given rise to a whole range of litigations.

Bail litigation and personal liberty

The Family Courts Act is not the only legislation which has defects in its design and architecture. There are several other enactments which appear to have been pushed in haste without assessing the impact and ramifications. A mere laudable object of legislation is not a guarantee that it will attain its stated objective. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (SC/ST Act), enacted with the intent of safeguarding and protecting the marginalised communities, has similar intrinsic shortcomings. The provisions of any law are susceptible to misuse and this Act is not an exception.

In case of blatant misuse of penal provision, those facing prosecution under general law like IPC, can move the courts for anticipatory bail to safeguard their personal liberty. This statutory safeguard is not available under the SC/ST Act, as Section 18 specifically bars it. The Supreme Court in several cases has noted misuse of the provisions of the SC/ST Act and conceded the right to anticipatory bail, if a prima face case was not made out. In recent cases of Shajan Skaria v. State of Kerala3. The Supreme Court observed:

29. However, over a period of time, the courts across the country started taking notice of the fact that the complaints were being lodged under the Act, 1989 out of personal and political vendetta. The courts took notice of the fact that the provisions of the Act, 1989 were being misused to some extent for purposes not intended by the legislation. To overcome the bar of Section 18 of the Act, 1989, the persons against whom such complaints were being lodged started invoking the writ jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution.

30. Taking note of the aforesaid, this Court in Subhash Kashinath Mahajan v. State of Maharashtra4, while quashing the proceedings instituted against the appellant therein under the provisions of the Act, 1989 thought fit to issue the following directions:

79.1. Proceedings in the present case are clear abuse of process of court and are quashed.

79.2. There is no absolute bar against grant of anticipatory bail in cases under the Atrocities Act if no prima facie case is made out or where on judicial scrutiny the complaint is found to be prima facie mala fide.

79.3. In view of acknowledged abuse of law of arrest in cases under the Atrocities Act, arrest of a public servant can only be after approval of the appointing authority and of a non-public servant after approval by the Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) which may be granted in appropriate cases if considered necessary for reasons recorded. Such reasons must be scrutinised by the Magistrate for permitting further detention.

79.4. To avoid false implication of an innocent, a preliminary enquiry may be conducted by the Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) concerned to find out whether the allegations make out a case under the Atrocities Act and that the allegations are not frivolous or motivated.

79.5. Any violation of Directions 79.3 and 79.4 will be actionable by way of disciplinary action as well as contempt.

79.6. The above directions are prospective.

Section 18 of the Act bars anticipatory bail of a person accused of committing an offence under the Act. Meaning thereby, if an FIR is lodged with allegation of offence under this Act, the only remedy for the person is to move for regular bail after he is arrested or surrendered before the Court and taken into custody. It has in many cases become a tool to send the adversaries behind the bar in a dispute notconnected with the caste of a person/complainant. Relying on the principles of law settled through a catena of judgments of the Supreme Court related to the provisions of the Act, the High Courts across the country saw a significant number of petitions under Section 482 CrPC for quashing of FIR/proceeding initiated under this Act.

Despite the ruling of, the Supreme Court that where prima facie case is not made out, anticipatory bail application shall be maintainable, due to embargo under Section 18 of the Act, the trial courts are hesitant in allowing applications for anticipatory bail and they are mostly rejected. Against the order of rejection, appeals are preferred before the High Court under Section 14-A of the Act. Furthermore, Section 15-A(5) of the Act mandates that no order can be passed without hearing the victim or his dependent.

As a result, the High Courts are facing a large number of criminal appeals arising out of rejection of anticipatory bail application by the trial courts, and before these criminal appeals can be heard, cases are adjourned for service of notice on the victims/complainants. The end result is the same, with the difference that the relief of anticipatory bail is now granted by the High Court and not the District Courts. The bar under Section 18 of the Act has served only as a tool for procrastination and flooding the docket of the High Courts.

Bihar goes dry

In Bihar, the Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act, 2016 was enacted in public interest with the objective of preventing the manufacture, possession, etc. of any intoxicant, liquor, hemp. To ensure deterrence of such activities, the Act provided for harsh punishments including life imprisonment, and in some cases provisions for even death sentences have been made.

Notwithstanding anything in the CrPC or the punishment of any offence under Section 83, Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act, 2016 mandates that all the offences under the Act would be triable exclusively by the Court of Session. Furthermore, Section 84 of the Act provides for the establishment of Special Courts for the trial of the offences under the Act. It is incomprehensible that Section 84(3) stipulates that, the trial under this Act of any offence by the Special Court shall have precedence over the trial of any other case against the accused in any other court (not being a Special Court) and shall be concluded in preference to the trial of such other case.

The legislative impact of the 2016 Act appears to have been completely lost sight of. This Act is part of a trend to provide enhanced stringent punishments based on the misconceived notion that increasing the punishment will increase its deterrent effect. As noted by the Supreme Court in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab5, in 1975, Robert Martinson, a sociologist, published the results of a study he had made in New York regarding the rehabilitation of prisoners wherein he had concluded that the certainty of punishment, rather than the severity, is the most effective crime deterrent.

The object of a penal legislation cannot be achieved merely by providing for harsh punishments, without ensuring that the criminal proceedings reach their logical conclusions through an effective and efficient process. While enhancing punishment and making offences exclusively triable by the Court of Session, what is overlooked is that trials in all cases do not conclude a litigation. It attains finality only after appeal. If an offence is triable by Magistrate, appeal will be maintainable before the Sessions Judge and only revision on question of law can be filed before the High Court. In case of any offence being triable by the Sessions Court, appellate forum becomes the High Court. Can the High Courts with a limited number of sanctioned strength of Judges hear and dispose of the deluge of new types of appeals arising from it, in a timely manner? This is a question policymakers do not think over while bringing new legislation.

By making the offence under the Bihar Prohibition Act, 2016 Sessions triable, has unintentionally opened the flood gate for appeals and revisions which the High Court will be grappling with in near future. The provision that trial of cases under this Act of a particular accused will have precedence over other cases pending against him is intriguing. Does it mean if an accused is facing trial for offences like murder, rape, dacoity and cases of the like, they have to be put in the backburner?

Logic of Special Courts

There is a veritable proliferation of Special Courts to expedite the adjudicatory process. The special feature of these Special Courts is that they are practically not special, except for their name. Sentences are enhanced and the Presiding Officers of such courts are usually in the rank of District and Sessions Judge. In effect, what it entails is that apart from the offences under the IPC, there can be a Special Court having District Judges as Presiding Officers for all other offences.

Under, the Electricity Act, 2003, provisions for Special Courts require the Presiding Officers to be of the rank of District Judges for offences under the Act, the punishments for most of which are of fine or imprisonment up to three years.

There are numerous other legislations which provide for the establishment of Special Courts, some of which are — the Companies Act, 2013, the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, the Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, 2002, the National Investigation Agency Act, 2008, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012, the Customs Act, 1962, the Income Tax Act, 1961, the Essential Commodities Act, 1955, the Arms Act, 1959, the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957, the Fugitive Economic Offenders Act, 2018. Such a huge number of legislations setting up Special Courts indicates that for every type of offence, a Special Court can be constituted.

It is also relevant to note that though these legislations provide for the establishment of Special Courts, what is being done at ground level is that without strengthening the infrastructure or increasing the sanctioned strength of Judges, the existing courts are “designated” as Special Courts, thereby overburdening a particular court with additional charge.

The old model

Ideally whether it is a civil, criminal or a land revenue dispute, the old model of adjudication was to see its conclusion at the District Court level. In conformity with this model, all the land revenue, land settlement and land consolidation matters concluded at the level of Commissioner. Civil disputes could be instituted in the Court of the lowest grade competent to try it, and the appeals were disposed of and concluded at the level of District Judge. It may be somewhat interesting to know that the Court of Munsifs even passed an order of injunctions staying transfer of government servants in injunction suits.

Those who have worked on the civil side in the High Court, will appreciate that the perennial source of delay is service of notice on the other side in hearing an appeal or revision. Under the old model, the system of service of notice on respondents, was much easier and streamlined. Order 41 Rule IX CPC provides that the Court from whom an appeal lies shall entertain the memorandum of appeal and shall endorse thereon the date of presentation and shall register the appeal in a book of appeal for that purpose. Under Order 41 Rule XIV, notice of the day fixed under Rule XII shall be affixed in the appellate courthouse. Further notice can be served on the counsel representing the party before the trial court in terms of Order 3 Rule V. Everything took place in the same campus of the civil court. However, when the appeal is before the High Court, even a simple process of serving notice on parties becomes cumbersome and a time-consuming process.

In criminal cases emphasis was to conclude trial before the Courts of Magistrates even for offences where the maximum sentence of imprisonment that could be imposed was more than the sentencing power of the Magisterial Court. Provisions under Sections 323 and 325 CrPC ensured that in appropriate cases, the Magistrate can forward the case to the Chief Judicial Magistrate (CJM) or to Court of Session, where it felt the need to do so on the point of sentence or trial. All this was intended to ensure that trial was held in majority of the cases by the Court of Magistrate and the appeal lied before the Sessions.

Abandoning this model has resulted in a situation where trial of large numbers of cases is not held by the Courts of Magistrate, but by Sessions Courts, consequently they do not conclude at the District Court level, but spill over to the High Court level in appeal resulting in its delay in final conclusion.

Way forward

In conclusions following recommendations are being made for course correction:

1. Legislative enactments should preserve the pyramidal model of adjudication where most of the litigation attains its finality at the District Court.

2. District Courts need to be trusted, strengthened, and expended in its sanctioned strength to make justice dispensation effective at the grass root level.

3. Increase the sanctioned strength of the Civil Judge Junior Division and Civil Judge Senior Division so that they become the mainstay of adjudication of civil and criminal cases, with appellate jurisdiction vested in the District Courts.

4. The Family Courts Act needs a relook and the earlier model where the maintenance cases under the CrPC were adjudicated by the Judicial Magistrates and matrimonial suits by the Courts of Sub-Judges may perhaps be restored. In some large districts, where there is a significant number of pendency, Special Family Courts with Presiding Officers in the rank of Sub-Judges can be established.

5. Section 18, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, needs a relook and provision for anticipatory bail needs to be restored.

6. While enhancing sentences of offences and changing the forum of trial to the Sessions Court, resultant increase of pendency of appeals in the High Courts need to be factored.

7. The High Court should ideally be confined to constitutional matters, first appeals and sessions appeals and to second appeals and revisions, limited to questions of law.

8. In the process of legislative impact assessment, those having a modicum of experience of serving at the District Court level, should also be consulted.

*Sitting Judge of the High Court of Jharkhand. Author can be reached at: gautamhcranchi@gmail.com.

1. Lok Sabha, starred question 113, answered by Arjun Ram Meghwal on 9-2-2024, available at <https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1715/AS113.pdf?source=pqals>.

2. High Court of Jharkhand, Ranchi, available at <https://jharkhandhighcourt.nic.in/justice_clock/dist_jclock.php> assessed on 24-7-2024.

4. (2018) 6 SCC 454., 513, paras 79.1-79.6.