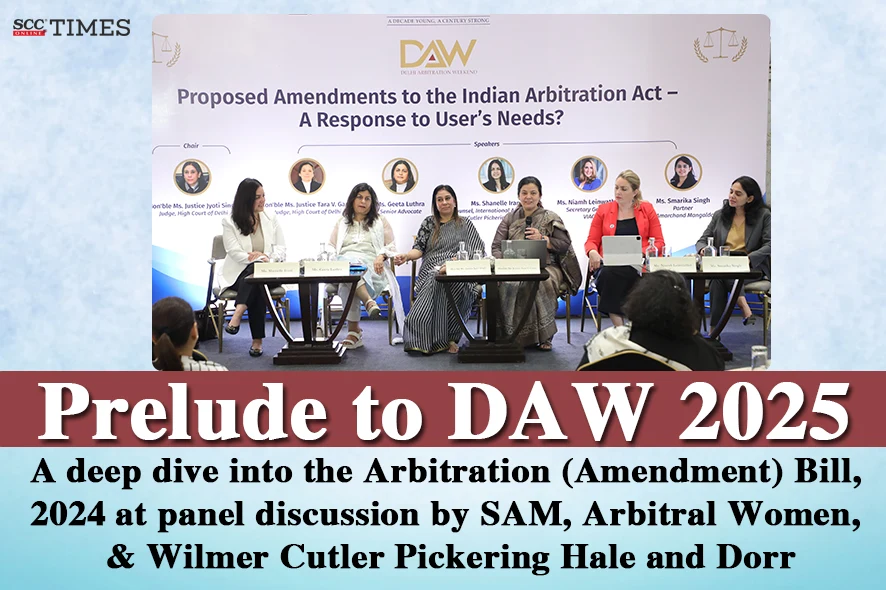

On 18.09.2025, Arbitral Women, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co., and Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr, organised a panel discussion on “Proposed Amendments to the Indian Arbitration Act – A Response to User’s Needs?”.

The panel chaired by Justice Jyoti Singh, Judge, Delhi High Court, and moderated by Ms. Shanelle Irani, Counsel, International Arbitration, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr; comprised of eminent panellists namely, Justice Tara V. Ganju, Judge, High Court of Delhi; Ms. Geeta Luthra, Senior Advocate; Ms. Niamh Leinwather, Secretary General, Vienna International Arbitral Centre; and Ms. Smarika Singh, Partner, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.

Kicking off the session, Ms. Shanelle Irani asked Justice Jyoti Singh to provide the audience with a summary or overview of the draft Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024 (‘the draft bill’).

Responding to the question, Justice Singh briefly explained the following changes introduced by the draft bill:

-

Statutory recognition of online arbitration: The draft bill embraced technology as it now included online arbitration within the definition of arbitration and allowed execution of the arbitration agreement via digital signatures.

-

Emergency Arbitration: It provided for emergency arbitration, which would allow urgent relief before a formal arbitral tribunal was even constituted.

-

Section 9 was amended to include Section 9A.

-

Seat Centric Jurisdiction: The jurisdiction would now be seat-centric. The bill provided for the mutual consent selection of a seat by the parties; if that fails, then by the arbitral tribunal, and if that too fails, the matter would reach the Court. Justice Singh remarked that this amendment would align domestic with international arbitration and address the heavily litigated aspect of territorial jurisdiction.

-

Stricter Timelines: Strict timelines were established at various stages to expedite the proceedings, starting from reference to the constitution of the tribunal to the challenges, and so on and so forth.

-

Institutional Arbitration: Institutional Arbitration was empowered through an amendment to Section 29A(4), wherein, in addition to courts, institutions also have the power to extend mandates. This would allow parties to opt for either forum to get mandate extensions and reduce judicial interference.

-

Schedule 4 had been omitted.

-

Draft Model Agreement: A draft model agreement would be prepared, serving as a template for those who lacked professional assistance.

-

Stamping: The draft bill provided that the day the award is issued, it would have to be stamped. As per Justice Singh, this would reduce a lot of delays in the enforcement stage.

-

Section 34: This section had been amended to enlarge the scope, and it allowed for partial setting aside of an award.

Justice Singh concluded by remarking that “the takeaway is that this will expedite, modernize, and systemize the arbitration proceedings.”

In the same vein, Ms. Irani asked Justice Tara V. Ganju whether more amendments were needed in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (‘the Act’), despite the draft bill being the fourth one in the last 10 years. Justice Ganju answered in the affirmative and remarked, “Our arbitration laws have evolved steadily to create a reliable, efficient, and internationally respected dispute resolution system.”

She drew a timeline of the amendments with the 1996 act being based on the UNCITRAL model, the 2015 amendment introducing timelines, clarifying grounds for challenging arbitrators, and promoting institutional arbitration, the 2019 amendment strengthening confidentiality, refining arbitrator appointment processes, and making deadlines stricter, and lastly, the 2021 amendment removing the Eight Schedule and expanding party autonomy. Regarding the draft bill, she highlighted the various changes made in the Act, such as dropping the word ‘conciliation’ from the Act, the introduction of seat-centric jurisdiction, and the expedition of timelines.

Adding to the discourse, Ms. Smarika Singh asked Ms. Geeta Luthra whether the draft bill’s reduction of the timelines addresses the users’ needs. Ms. Luthra responded that though 30 days was a very compact timeline, it was a good suggestion. However, the time period of 60 days under Section 37 of the Act was slightly more difficult, considering the heavy Court docket. Additionally, there was no punishment or penalty for not deciding within the said timeline. Thus, she concluded that if it was directory and not totally mandatory, then it was welcome because it was a tall order for the Benches and the law officers.

From the Court’s perspective, Justice Ganju added that in a Section 37 stage, the Court is re-examining everything again after an award had been passed and altered under Section 34. She questioned how the application would be adjudicated in 30 days in this scenario, where there might be parts of the award that have been modified or set aside.

Regarding the enhancement of the powers of the Arbitration Council (‘the Council’) in the draft bill, Ms. Irani asked Ms. Niamh Leinwather whether there was a potential risk of over-centralization of bureaucratic hurdles with the Council’s expanded role?

At the outset, Ms. Leinwather commended the efforts undertaken by India to reform, promote institutional arbitration, and make India the global hub for arbitration. Answering the question, she agreed that it was yet to be seen how the Council would pan out in practice and what kind of role it would take. Other international arbitral institutions do not have a regulatory body, so one could question whether it was necessary to have such a regulation or centralization. However, maybe it could contribute to the interest of promoting arbitration, making it more credible and reliable, and promoting institutional arbitration.

Furthermore, she spoke about the need for regulations, the importance of transparency in the procedures and criteria adopted by the regulatory body, and the aspect of taking inputs from stakeholders, while making amendments, as to what was required in practice. Thus, she concluded that central oversight and regulation could be useful in promoting institutional arbitration, but it could also stifle the process. It would have to be seen how it was executed and implemented at the end of the day.

Taking the discussion forward, Ms. Irani asked Ms. Luthra about the power of the Arbitration Council to suspend and withdraw recognition of arbitral institutions. She questioned whether this could lead to complexities if an institution’s license is withdrawn in the middle of an arbitration or in the middle of many arbitrations that they are administering.

Ms. Luthra responded that it was, of course, important to have an institution that recognised good arbitrators and ensured that arbitrators were internationally cross-border trained. However, in the case of institutions, baby steps had to be taken before considering derecognition of an arbitral institution. She added that, of course, there would have to be rules for derecognition of an arbitrator when he is in the middle of proceedings because if an arbitrator were removed mid-way, then the whole purpose of certainty, autonomy, and efficiency of arbitration would be lost.

Addressing Ms. Singh, Ms. Irani asked how likely the domestic ad hoc tribunals were to, voluntarily, apply the model rules made by the Council.

Ms. Singh replied that this issue had to be viewed from the vantage point that, despite the prevalence of so many arbitral institutions, Indian clients still preferred ad hoc arbitrations. This was because of a due process paranoia, as recognised by the 2017 Shri Krishna Committee, because the tribunals were following strict CPC procedures and evidence. This procedure was not always preferred in some arbitrations, such as infrastructure ones, where the documents were in tens of thousands.

Similarly, she added, it was recognized that the ad hoc arbitrations were not functioning in a manner that the parties wanted, and there was an absence of uniform model laws. In fact, despite the parties having the autonomy to ask the tribunal to follow certain procedures, Indian counsels or parties usually did not ask for the same. Thus, Ms. Singh opined that given this voluntary adoption of model guidelines, it would have to be seen how seasoned tribunals and practitioners will adopt them because they may still not want to give up the autonomy.

“The principal value actually lies in not replacing party autonomy here, but providing a set of rules that can be a guiding factor for the tribunal at large.”

– Ms. Smarika Singh, Partner, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.

Thereafter, the panellists traversed many aspects of the topic, such as enforcement of model rules without an institution, benefits of an institutional arbitration, non-application of the draft bills’ Section 9A to the emergency awards passed by foreign-seated tribunals, enforceability of foreign emergency arbitration awards, assigning an identification number to arbitration proceedings, appellate arbitral tribunal, third party funding, and much more.

In conclusion, Ms. Irani thanked the stellar panellists and the audience for being a part of the enlightening discussion.