As a general rule under the CrPC and now under the BNSS as well, there is a duty cast upon a police officer to mandatorily register an information which discloses the commission of a cognizable offence.

Generally, to put criminal law into motion, a first information report (FIR) needs to be registered. Section 173, Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 (BNSS) contains the procedure on how to register an information which discloses commission of a cognizable offence. Section 173 BNSS corresponds to Section 154, Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (CrPC). The section casts a duty upon the police officer to register every information which discloses a cognizable offence. The section also provides remedies in case the police officer does not register the FIR as presented by the victim or the informant.

As a general rule under the CrPC and now under the BNSS as well, there is a duty cast upon a police officer to mandatorily register an information which discloses the commission of a cognizable offence. There was no exception to this rule, apart from the exceptions laid down in Lalita Kumari v. State of U.P.1, in which it was possible for an officer in certain cases to hold a preliminary enquiry only to ascertain whether the information received by him discloses the commission of a cognizable offence. This position of law has undergone a change in the newly introduced BNSS. Now one exception is carved out under Section 173(3) with respect to the general rule. For the benefit of readers, it would be necessary to lay down Section 173(3) BNSS, which is as follows:

173. Information in cognizable cases.—(3) Without prejudice to the provisions contained in Section 175, on receipt of information relating to the commission of any cognizable offence, which is made punishable for three years or more but less than seven years, the officer in charge of the police station may with the prior permission from an officer not below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police, considering the nature and gravity of the offence,—

(i) proceed to conduct preliminary enquiry to ascertain whether there exists a prima facie case for proceeding in the matter within a period of fourteen days; or

(ii) proceed with investigation when there exists a prima facie case.

This sub-section gives a discretion to the police officer who receives an information which discloses the commission of a cognizable offence not to straightaway register the FIR in certain cases, i.e., offence punishable with three years or more but less than seven years, but to hold an inquiry in order to find out whether the information received by him constitute a prime facie case. With this background in our mind, we now move on to the issues for the consideration under this article:

1. Whether the word “or”, which is placed in between the two clauses of Section 173(3) BNSS, should be read plainly as disjunctively or should it be read as “and”?

2. What is the remedy available to the victim/informant, if the police officer does not register the FIR after finding that there is no prima facie case?

Legal consequences of reading “or” plainly

If we read the word “or” disjunctively, the following results emanates—

In cases where the offence, disclosed from the information provided by the victim/informant, is punishable with three years or more but less than seven years, the police officer has been given a discretion not to straightaway register an FIR. The police officer can proceed in either of the two ways:

1. the police officer can, with the permission of an officer not below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) make an inquiry to find out if the information provided makes out a prima facie case or not, and he needs to complete the inquiry within a period of 14 days; or

2. the police officer can, with the permission of an officer not below the rank of DSP, proceed with the investigation when there exists a prima facie case.

It is important to note at this juncture that sub-section (3) is an enabling provision, and the opening line of the sub-section starts with “without prejudice to the provisions contained in Section 175”. Section 175 BNSS mainly states that the police officer has the power to investigate any cognizable offence without any permission from anyone. So, it is important to note that it is upon the police officer’s wisdom if he wants to avail the course under Section 173(3) or whether he wants to straightaway lodge an FIR and investigate into the matter.

The problem with this interpretation

If the police officer chooses the first option and go for the inquiry, it is well and good, but the problem lies if the police officer without opting for the first option decides to exercise his power by opting the second option, i.e., to investigate if there exists a prima facie case. For exercising the second option he has to seek permission from the DSP. It is a baffling thing that when the whole sub-section is without prejudice to Section 175 (which gives the power to the police officer to investigate any cognizable offence without any permission), still if there exists a prima facie case the police officer has to take consent from the DSP. It is an inconsistency on the face of it, and this interpretation makes the section partly unworkable. The consent from the DSP is needed only to do a preliminary enquiry in order to find out whether there exists a prima facie case or not, and not for investigating if there exist one.

There is one more problem with this interpretation. As the police officer has been given two choices under Section 173(3), if he chooses to avail the second option (i.e. proceeding to investigate if prima facie case exists), it is necessary for him to ascertain that there exists a prima facie case and then only he can investigate and for ascertaining whether there is prima facie case or not, he has to necessarily make an enquiry [as contemplated by Section 173(3)(i)]. So, the police officer cannot directly avail the second option in spite of the usage of the word “or” between the two sub-clauses to Section 173(3).

Legal consequences of reading “or” as “and”

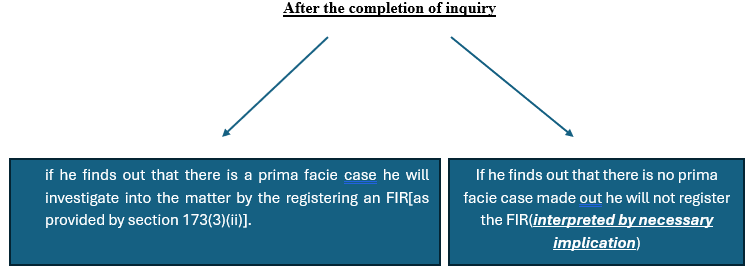

If we read the word “or” as “and”, the following results emanates—

In cases where the offence, disclosed from the information provided by the victim/informant is punishable with three years or more but less than seven years, the police officer has been given a discretion not to straightaway register an FIR. The police officer may, with the permission of an officer not below the rank of DSP, make an inquiry to find out if the information provided makes out a prima facie case or not and he needs to complete the inquiry within a period of 14 days.

This interpretation echoes with the intention of legislature. The legislature introduced Section 173(3) with the intention of giving the police officers a chance to verify the information (to some extent) received by them regarding certain trivial cognizable offence, and not to register an FIR straightway in frivolous cases,2 having regard to the nature and gravity of offence. The legislature saved the general powers of the police officers to investigate any cognizable offence, that is the reason Section 173(3) starts with “without prejudice to the provisions contained in Section 175”.

Courts power to read “or” as “and”

Where the language of a statute is plain and simple, the general rule is to interpret it plainly. However, when the plain meaning of the words planted by the legislature produces inconsistency with other provisions and makes the section unworkable, it is necessary for the courts to find out the intent of the legislature and to modify the meaning of the words in the section to bring the section in conformity with the intent of the legislature. It can be done by rejecting the words altogether; or by interpolating other words. It has been accepted that “to carry out the intention of the legislature, it is occasionally found necessary to read the conjunctions “or” and “and” one for the other.3

Coming to the issue at hand it would be apposite for the courts to read “or” occurring under Section 173(3) as “and” in order to make the section fully workable and its objective achievable.

Remedy available to the victim/informant if the police officer refuses to register an FIR after a finding that no prima facie case is made out

It would be fruitful to lay down Section 173(4) in order to address the present issue, it is as follows:

173. Information in cognizable cases.—(4) Any person aggrieved by a refusal on the part of an officer in charge of a police station to record the information referred to in sub-section (1), may send the substance of such information, in writing and by post, to the Superintendent of Police concerned who, if satisfied that such information discloses the commission of a cognizable offence, shall either investigate the case himself or direct an investigation to be made by any police officer subordinate to him, in the manner provided by this Sanhita, and such officer shall have all the powers of an officer in charge of the police station in relation to that offence failing which such aggrieved person may make an application to the Magistrate.

Why an application to the Superintendent of Police will not suffice

As a general rule, the police officer is duty-bound to register the information which discloses a cognizable offence. This proposition of law is stated under Section 173(1). If the police officer fails in his duty, the victim has a remedy provided under Section 173(4). The victim has to file a written application to the Superintendent of Police (SP). If the SP also fails in his duty then he can file an application to Magistrate. As already discussed, Section 173(3) is an exception to Section 173(1). So, in certain trivial cognizable offences [provided under Section 173(3)], the police officer will not be bound to register the FIR and he can inquire into the information provided to him.

From the above said discussion, it is clear as a noon day that a victim cannot be said to be aggrieved, if he gives information disclosing a cognizable offence (which is punishable with three years or more but less than seven years) and the police officer refuses to register his FIR. The reason being the police officer has got a discretion to do so. There are two more reasons why the abovestated aggrieved person cannot avail his remedy under Section 173(4):

1. The opening line of Section 173(4) BNSS refers to a person aggrieved by a refusal on the part of police officer to record the information provided under sub-section (1). It does not mention “person aggrieved under Section 173(3)”.

2. Even if the aggrieved person writes an application to the SP, as stated in sub-section (4) itself, he can only see if the information discloses a cognizable offence. On the other hand, when the police officer chooses to inquire into the information provided by the informant/victim, it means that the information already discloses that it is a cognizable offence. This is evident from the opening line of Section 173(3), i.e., “on receipt of the information relating to the commission of a cognizable offence”. So, it would be a futile exercise if the aggrieved person files an application before the SP.

Remedy — before the Magistrate

The only remedy which the abovestated aggrieved person has is to directly file an application in accordance with the procedure laid down under Section 175(3) BNSS. Section 175(3) BNSS reads thus:

175. Police officer’s power to investigate cognizable case.—(3) Any Magistrate empowered under Section 210 may, after considering the application supported by an affidavit made under sub-section (4) of Section 173, and after making such inquiry as he thinks necessary and submission made in this regard by the police officer, order such an investigation as above-mentioned.

So, the victim/informant aggrieved by the police officer not registering the FIR after finding out that there is no prima facie case, can move an application before the Jurisdictional Magistrate and seek investigation into the matter.

*Practicing as an advocate in Delhi, LLM (Delhi University). Author can be reached at: rajattomar37@gmail.com.

1. (2014) 2 SCC 1 : (2014) 1 SCC (Cri) 524.

2. Imran Pratapgadhi v. State of Gujarat, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 678.

3. Sir Peter Benson Maxwell, Maxwell on Interpretation of Statutes (11th Edn., London, 1962).

Insightful and well-articulated.