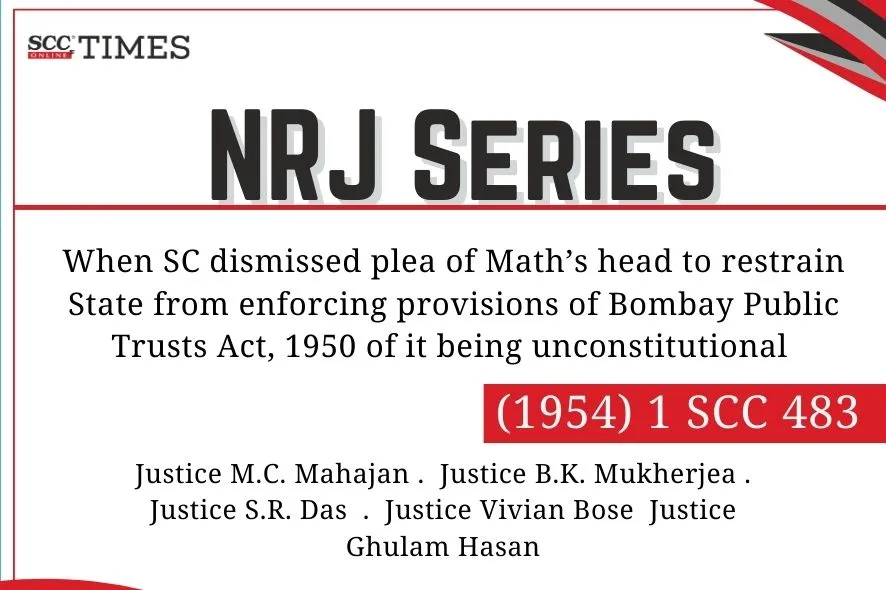

Supreme Court: In the present case, a petition under Article 32 of the Constitution was filed praying for a writ, in the nature of mandamus, against the State of Bombay and the Charity Commissioner of that State directing them to forbear from enforcing against petitioner the provisions of the Bombay Public Trusts Act, 1950 (‘1950 Act’), on the ground that the 1950 Act was ultra vires the Constitution as it offended fundamental rights of petitioner under Articles 25, 26, and 27 of the Constitution. The 5-Judges Bench of M.C. Mahajan, CJ., B.K. Mukherjea*, S.R. Das, Vivian Bose, and Ghulam Hasan, JJ., opined that petitioner could claim exclusion or exemption from operation of the 1950 Act in an appropriate manner and in case of applicability of the 1950 Act to him, his case would be governed by earlier decisions of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court held that it would be open to petitioner to challenge the enforcement of those provisions of the 1950 Act which have been held to be invalid in earlier Supreme Court’s decisions.

Background

Petitioner was the Mathadhipati of a Math, which was an institution belonging to the Madhwa Sect of the Gowd Saraswat Brahmins and although its headquarters were at Benaras and the Mathadhipati resided there for the most part, the endowed properties attached to the Math were scattered all over India and there were rest houses, shrines, and other sacred institutions situated at various places within India, which were additions to the main institution. There were sacred sites known as ‘Vrindavans’, wherein the mortal remains of two of the previous Swamis of the Math who gave up their bodies at that place, were preserved and besides these, there are two small properties within the State of Bombay, whose total assessment was around Rs 77 a year.

The State Legislature of Bombay passed the Bombay Public Trusts Act in 1950 and the said Act received the assent of the President on 31-05-1950. By a Notification dated 30-01-1951, the 1950 Act was brought into force on and from 01-03-1951, and its provisions were made applicable to all Maths within the State.

Petitioner submitted that the provisions of the 1950 Act were destructive of his fundamental rights as the head of a Math and representative of a religious denomination guaranteed under Articles 25, 26, and 27 of the Constitution and they reduced him to the position of a servant under the Charity Commissioner. It was stated that under Section 18 of the 1950 Act, it was incumbent on every trustee of every public trust (and a Mathadhipati was brought into this category), to apply for registration of the trust in the manner laid down in the rules. Under Section 18(2), the application had to be made to the Deputy or Assistant Charity Commissioner of the region or sub-region within the limits of which the trustee had an office for the administration of the trust/trust property/substantial portion of it was situated and the failure to comply with the said provision constituted an offence punishable under Section 66.

It was submitted that although the Math and its endowed properties were situated outside the State of Bombay, the Charity Commissioner might, by taking advantage of the artificial and extended definition of Math given in Section 2(9) of the 1950 Act, enforce the provisions of the 1950 Act against him and the institution which he represented. Further, non-compliance of the said provision of the 1950 Act might result in petitioner’s humiliation and make him liable to criminal prosecution. Thus, petitioner addressed a letter to the Government of Bombay on 29-12-1950 stating that the 1950 Act was not applicable to “Vrindavans” at Bombay and that an order might be passed accordingly.

On 03-03-1953, the Government wrote a letter stating that petitioner’s request for exemption was under consideration. Petitioner replied to this letter stating that what he claimed was total exclusion and not exemption and that unless within a week from 25-03-1953 it was made clear that the 1950 Act was inapplicable to the Math, proceedings would be instituted. As no reply was received, the petitioner filed the present petition. Petitioner challenged the constitutional validity of the 1950 Act on the ground that its provisions conflict with the fundamental rights of petitioner and prayed that even if the 1950 Act was not ultra vires or void, it could have no application to the Kasi Math situated at Benaras in the Uttar Pradesh or to petitioner who was the Mathadhipati or head or to any of the properties or places of worship in addition to the institution.

Analysis, Law, and Decision

The Supreme Court opined that as petitioner contended that he did not come within the purview of Section 18(2) at all, he could raise this point in an appropriate manner when the said provision was attempted to be enforced against him.

The Supreme Court opined that the question of the validity of the different provisions of the 1950 Act was discussed in Ratilal Panachand Gandhi v. State of Bombay, (1954) 1 SCC 487 and the provisions of the 1950 Act which were invalid by reason of them conflicting with fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution had been pointed out.

The Supreme Court opined that as only a very few provisions of the 1950 Act had been held to be unconstitutional in earlier decisions of the Supreme Court, petitioner could not have filed a writ based on that decision against the Charity Commissioner or the State Government to restrain them from enforcing the provisions of the whole 1950 Act.

The Supreme Court observed that petitioner seemed anxious to have a decision that the 1950 Act was not applicable to the small endowments of the Math which were situated within the State of Bombay. The Supreme Court held that it would be open to petitioner to claim either exclusion or exemption from the operation of the 1950 Act in an appropriate manner and if, however, the 1950 Act was held applicable to him, his case would be governed by the decision in the Civil Appeals Nos. 1 and 7 of 1953 and it would be open to him to pray for writs against the enforcement of the particular provisions of the 1950 Act which this Court had held to be invalid, if at all they are sought to be enforced against him. Thus, the Supreme Court dismissed the present petition.

[Sudhindra Tirtha Swami v. State of Bombay, (1954) 1 SCC 483, decided on 18-03-1954]

*Judgment authored by: Justice B.K. Mukherjea

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For the Petitioner: M.K. Nambiar, Senior Advocate (K.P. Madhava Rao and Rajinder Narain, Advocates, with him)

For the Respondents: M.C. Setalvad, Attorney General for India and C.K. Daphtary, Solicitor General of India (G.N. Joshi and Porus A. Mehta, Advocates, with him)

**Note — Bombay Public Trusts Act, 1950

It was enacted to regulate and to make provisions for the administration of public, religious and charitable trusts in the State of Bombay. It applied to the endowments of all communities and by virtue of this Act, the Government assumed the duty of directly supervising the administration of endowments.

The Bombay model, followed by MP, Rajasthan, and Gujarat provides for a distinct approach to deal with public trusts. Public trust means an express or constructive trust for either a public, religious or charitable purpose or both and includes a temple, math, a wakf, church, synagogue, agiary or other place of public religious worship, a dharmada or any other religious or charitable endowment and a society formed either for a religious or charitable purpose or for both and registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860. Detailed provisions about charity commissioner’s power to register the public trusts, call for accounts, approve annual budget, get auditing of the trust, suspend, or dismiss defaulting trustees, appoint new trustees, inspect, and investigate, stop wastage or alienation of trust property, and give notice for cy pres application of property.