“Criminalising consensual same sex in private, between adults is not in the public interest. Such criminalization….disproportionally impacts on the lives and dignity of LGBT persons. It perpetuates stigma and shame against homosexuals and renders them recluse and outcasts…. Such penal provisions exceed the proper ambit and function of criminal law in that they penalise consensual same sex, between adults, in private, where there is no conceivable victim and complainant.”

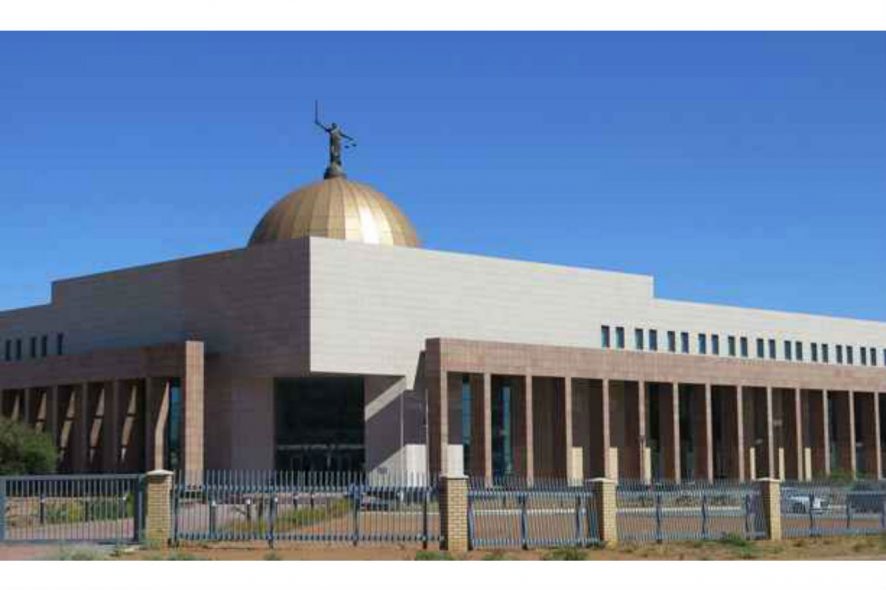

Botswana High Court: In a landmark ruling which came as a big victory for LGBTQ rights in Africa, a Full Bench of M. Leburu, A.B. Tafa, J. Dube, JJ. decriminalized homosexuality and struck down provisions prohibiting consensual sexual intercourse between homosexuals, holding the same to be discriminatory and ultra-virus.

Applicant herein, was a university student and a homosexual, who questioned Sections 164(a), 164(c) and 165 of the Penal Code, 1964 as being discriminatory and ultra-virus as these sections prohibited him from enjoying and engaging in sexual intercourse with a man. Botswana’s Penal Code, 1964, drawn up under British rule, outlawed “carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature”(Section 164), with those convicted facing up to seven years in prison; as well as “indecent practices between persons” in public or private (Section 167), punishable with up to two years in prison.

Applicant’s case was that the impugned provisions were unconstitutional and vague as they were not made for the peace, order and good governance and lacked clarity on the exact type of conduct that was being criminalized. He also contended that the impugned provisions violated his right and freedom to liberty, as they prohibited him from using his body from expressing sexual affection by the only means which was available to him as a homosexual. Applicant submitted that the impugned provisions perpetuated negative stigma against homosexuals and urged that the impugned sections should be struck down as unconstitutional and vague, particularly with respect to the meaning of “carnal knowledge” and “against the order of nature”.

Whereas the respondent’s case was that Sections 164 (a) and 164(c) of the Penal Code were not discriminatory as they were of equal application to all sexual preferences, and sexual orientation or being homosexual was not criminalized, rather it was certain sexual acts that were deemed against the order of nature were criminalized. The Attorney General’s contention was that the words used were clear and not vague and that they simply mean “anal penetration”, as was defined by the Court of Appeal in the case of Kanane v. State, [2003] (2) BLR 67 (CA). He submitted that applicant was free to engage in sexual activity as long as it was not sexual intercourse per anus; and this was a valid restriction as Section 15 of the Constitution of Botswana provided limitations on the enjoyment of fundamental rights.

Botswana High Court noted that same-sex activity was deemed morally unacceptable by the British and was hence, prohibited. Macaulay’s draft of Indian Penal Code, 1860 and particularly Section 377 IPC was copied in a large number of British territories, including Botswana. It was only after recommendations of the Wolfenden Committee Report, that the United Kingdom decriminalized same-sex sexual intercourse.

The Court observed that privacy is a cherished fundamental human right, and an important element of personal autonomy as it gave person space of being himself or herself without any judgment and allowed him to think freely without hindrance. It relied on Articles 1, 2 and 3 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights 1948 which protect the right to human dignity. It also referred Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966, which provide that- “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.”

The Court opined that while public opinion is relevant in matters of constitutional adjudication, but it is not dispositive; as such public opinion is trumped by the colossal human rights “triangle of constitutionalism”, namely liberty, equality and dignity. It observed that this triumvirate formed the core values of fundamental rights, as entrenched in Section 3 of the Constitution. Court also observed that it had been already settled principle that there must remain a realm of private morality and immorality which should not be the province of the law, where there was no victim or complainant and when such conduct was consensual.

Court relied on various judgments of the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Canada and also relied on the decision of Supreme Court of India in Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India, (2018) 10 SCC 791, in which Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code 1860, dealing with unnatural sex laws was read down and homosexuality was decriminalised. It was held in this case that sexual orientation of a person is an essential attribute of privacy and its protection lies at the core of fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 15 and 21 of Constitution of India.

Court also observed that the choice of a partner, the desire for personal intimacy, and the yearning to find love and fulfillment had universal appeal, and the State has no business to intrude into these personal matters and held that respondent gave no justification as to why a person’s right to privacy and autonomy was ought to be curtailed in relation to consensual acts done in private: and accordingly ordered that the word “private” must be severed and excised from Section 167 of the Penal Code.

Reliance was also placed on the UK’s Wolfenden Committee Report, on the basis of which it was opined that consensual adult sexual intercourse, between homosexuals, lesbians, transgenders, etc. do not trigger any erosion of public morality for such acts are done in private. It was observed that the realm of private morality and immorality should not be the province of the law, particularly where there is no victim or complainant and when such conduct is consensual.

In view of the aforesaid, Sections 164(a), 164(c) and 165 of the Penal Code were declared as ultra-virus to the Constitution, for being violative of Section 3 (liberty, privacy, and dignity), Section 9 (privacy) and Section 15 (discrimination) of the Constitution. The Court opined that the impugned provisions did not satisfy the proportionality test, and struck down those provisions. [Letsweletse Motshidiemang v. Attorney General Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals of Botswana (LEGABIBO), 2019 SCC OnLine BWHC 1, decided on 11-06-2019]