Supreme Court: In the present case, common grievance of the petitioners and applicants was regarding upper age limit for the ‘intending couple’, since the female could not be over and above 50 years of age and the male could not be over and above 55 years of age.

The Division Bench of B.V. Nagarathna* and K.V. Viswanathan, JJ., opined that the Surrogacy (Regulation) Act, 2021 (‘the Surrogacy Act’) was enforced when the intending couples in the present case, were in the midst a crucial phase i.e., at the stage of creation of embryos and freezing the same. The Court stated that the provision could not apply retrospectively because there was no age restriction when the intending couples commenced the surrogacy procedure. The Court stated that age restriction under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy Act would not be applicable to couples who froze embryos prior to commencement of law i.e., 25-01-2022. Thus, the Court held that Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy Act did not have retrospective operation and would not apply in the present case.

Background

In the present case, two writ petitions and one interlocutory application arose out of a set of similar but slightly differentiated facts. The common legal question was regarding the application of the age-restrictions on ‘intending couples’ under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy Act.

The common grievance of the petitioners and applicants, i.e. all the three intending couples, was regarding upper age limit for the ‘intending couple’, since the female could not be over and above 50 years of age and the male could not be over and above 55 years of age. The common contention of petitioners and applicant was that they had commenced the surrogacy procedures prior to the date of enforcement of the Surrogacy Act, i.e., prior to 25-1-2022 and therefore, when they were in the midst of such a procedure, the Surrogacy Act brought in an embargo in the form of the age-limit. As a result, they were barred from continuing the surrogacy procedure, although the same had been commenced much prior to the Act.

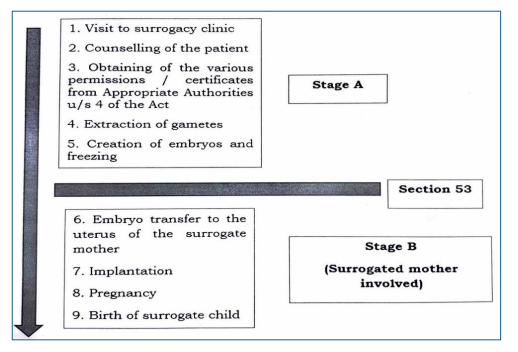

Process of surrogacy broadly entails the following stages:

Analysis, Law, and Decision

A. Surrogacy as an exercise of reproductive autonomy

The Court stated that it had often recognised the ‘reproductive autonomy’ as a part of the constellation of rights, afforded to everyone under Article 21 of the Constitution. The choice of a couple, medically incapable of conceiving/bearing children naturally, to pursue surrogacy procedures to procreate in the absence of binding regulations was an exercise of their decisional and reproductive autonomy.

The Court stated that at the time that intending couples, in the present case, generated and froze their embryos, they were qualified for surrogacy. Thus, they had right to surrogacy as a part of reproductive autonomy and parenthood. The Court stated that before 25-1-2022, there were no binding laws, certifications, etc. regarding age restrictions on intending couples wishing to avail surrogacy. Therefore, for couples above the (statutory) age limits under the Surrogacy Act, the right to access surrogacy or their entitlement to surrogacy was not conditional on their age and was freely available to couples under the prevailing law.

B. Retrospective application of age-restrictions

The real issue in the present case was whether a statutory regulation might apply retrospectively and frustrate a right under Article 21 of Constitution. The Court stated that the law does not impose any age restrictions on couples who wish to conceive and bear children naturally. In this regard, prior to the enforcement of the Surrogacy Act, intending couples in the present case, were on the same footing as couples who wished to conceive naturally. However, owing to medical reasons/disadvantages, they could not have children naturally. The Court stated it was not inclined to accept that, having exercised their freedom by initiating the surrogacy process, they could be denied the continued exercise of that freedom solely due to the age restriction under the Surrogacy Act.

The Court stated that for intending couples who undertook surrogacy procedures prior to the Surrogacy Act, age-related considerations were entirely their prerogative. Therefore, the Court stated that right to make autonomous decisions regarding the age at which one wished to pursue surrogacy, had vested in intending couples in the present case. Hence, since there was no manifest intention in the provisions of the Surrogacy Act to apply the age-limits retrospectively, the same was not permissible.

C. Operation of a statute

The Court stated that the controversy in the present case revolved around the concept of operation of statutes under principles of statutory interpretation. The dominant intention of the Legislature to be gathered from the language used, the object indicated, the nature of rights affected, and the circumstances under which the statute was passed. The Court stated that the provision could not apply retrospectively because there was no age restriction when the intending couples commenced the surrogacy procedure. The Surrogacy Act was enforced when the intending couple were during the procedure, at a crucial phase i.e., at the stage of creation of embryos and freezing the same. This was a sufficient manifestation of their intention.

The Court stated that the intending couples had an unfettered constitutional right when they commenced the process of surrogacy. The same could be curtailed only by reasonable restrictions and by not interpreting the Surrogacy Act unfairly. Therefore, the Court stated when there was no age restriction at Stage A, prior to the enforcement of the Act, now when the intending couples are at the threshold of Stage B, the age restriction under the Surrogacy Act cannot be permitted to operate retrospectively, so as to frustrate not just the surrogacy procedure but also their right to have a surrogate child or become parents.

Thus, the Court stated that age restriction under Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy Act would not apply, if an intending couple had —

-

commenced the surrogacy procedure prior to the commencement of the Act i.e., 25-01-2022; and

-

were at the stage of creation of embryos and freezing after extraction of gametes (Stage A); and

-

on the threshold of transfer of embryos to the uterus of the surrogate mother (Stage B)

Thus, the Court held that Section 4(iii)(c)(I) of the Surrogacy Act did not have retrospective operation and would not apply to the petitioners and applicants who were the intending couples. The Court clarified that it had not considered the validity of the age restrictions but only the applicability of the same to the petitioners and the applicants herein.

Justice K.V. Viswanathan’s view

K.V. Viswanathan, J., opined that for the intending couples, like the petitioners in this case, who froze the embryos and completed the Stage A process, there was no legal bar to resort to surrogacy. At a time when there was no disability attached, the petitioners exercised certain rights accrued to them once they finished the Stage A process. It is at this stage that the Surrogacy Act stepped in and created a disability for them by prescribing age limits.

Referring to Salmond on Jurisprudence, K.V. Viswanathan, J., opined that parenthood for the intending couple was not merely a hope or spes, but by completing the Stage ‘A’ process, certain vestitive facts did indeed crystallize and the Surrogacy Act does not seek to divest that. Thus, endorsing the operative part in this judgment, K.V. Viswanathan, J., stated that the ratio in Anushka Rengunthwar v. Union of India, (2023) 11 SCC 209 and Universal Imports Agency v. Chief Controller, Imports and Exports, 1960 SCC OnLine SC 42, have a great bearing on the present cases while grappling with the concept of vested rights and understanding the same.

[Vijaya Kumari S. v. Union of India, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 2195, decided on 9-10-2025]

*Judgement authored by- Justice B.V. Nagarathna

Advocates who appeared in this case:

For the Petitioner: Shikhil Shiv Suri, Sr. Adv.; Madhu Suri, Adv.; Jyoti Suri, Adv.; Ishita Ahuja, Adv.; Vibhor Choudhary, Adv.; Manek Kalyaniwalla, Adv.; Divya Swami, AOR; Mohini Priya, AOR

For the Respondent: Aishwarya Bhati, A.S.G.; Riddhi Jad, Adv.; Shivika Mehra, Adv.; Sudarshan Lamba, AOR; Rajat Nair, Adv.; Chitrangda Rashtrawara, Adv.; Ketan Paul, Adv.; Krishna Kant Dubey, Adv.; Mayank Pandey, Adv.; Aaditya Dixit, Adv.; Ravindra Sadanand Chingale, AOR; Shreya Munoth, AOR; Ameyavikrama Thanvi, AOR; Meenakshi S. Kamble, Adv.; Senha Deshmukh, Adv.; Hitesh Kumar Sharma, Adv.; Akhileshwar Jha; Ms. Swati Vishan, Adv.; Shreya Jha, Adv.; Ivan, AOR; Siddharth Agarwal, Adv.; Vivek Mathur, Adv.; Alok K Singh, Adv.; Anita Bafna, AOR; Mayilsamy K, Adv.; Naijal Kumar P, AOR; Kks Krishnaraj, Adv.; Arun Pandiyan S, Adv.; Dr. Gayathiri A S, Adv.; Thomas Oommen, AOR