The 5th edition of the Uzbekistan Arbitration Week (UzAW), 2025, was organised from 23 to 26-09-2025 in Tashkent by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Tashkent International Arbitration Centre (‘TIAC’) to bring together leading arbitration practitioners, judges, lawyers, and industry experts from around the world.

As part of UzAW 2025, a panel discussion on “Dos and Don’ts in International Arbitral Proceedings: Arbitrator Perspective” brought together leading arbitration practitioners from across the globe to share practical insights and strategies for navigating complex international arbitration. The session was designed to provide attendees with a deeper understanding of the impartiality and independence of arbitrators, cross-examination, AI and confidentiality concerns, and effective advocacy in international arbitral proceedings.

Moderated by Ms. Anna Arkhipova, Associate Professor, PhD, Deputy Head of the Maritime Arbitration Commission at the Russian Chamber of Commerce, the panel consisted of distinguished professionals namely, Mr. Shashank Garg, Senior Advocate, Chair ICC- India Arbitration Group; Mr. Kirill Laptev, AL Legal; Dr. Hamid Reza Oloumi Yazdi, Tehran Chamber of Commerce Arbitration Center; Mr. Nodir Yuldashev, Partner, Grata International; and Ms. Ketti Kvartskhava, Managing Partner, BLC Law Office.

Impartiality and Independence of Arbitrators in Investment Arbitrations

Enlightening the attendees on the topic of Impartiality and Independence of Arbitrators in Investment Arbitrations, Dr. Hamid Reza Oloumi Yazdi gave a detailed presentation.

1. Future of Investment Arbitration affecting the concepts of impartiality and independence

On this aspect, he ventured into the concerns surrounding transparency, Investor-State Dispute Settlements, public interests, similarity of issues in investment disputes, closed/limited circle of Arbitrators/Councils, the provisions and requirements of Bilateral Investment Treaties (‘BIT’), International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes’s (‘ICSID’) unique adjudication of challenges, and more.

2. ICSID Arbitration Rules-

Dr. Yazdi explored some key provisions of the ICSID Convention, 2006, which are as follows:

-

Impartiality- He referred to Article 14 of the ICSID Convention on impartiality, which provides that the persons designated to serve on the Panels of arbitrators or conciliators shall be persons of high moral character and recognized competence in the fields of law, commerce, industry, or finance, who may be relied upon to exercise independent judgment. Competence in the field of law shall be of particular importance in the case of persons on the Panel of Arbitrators. Similarly, Article 10 of the TIAC Rules, 2021, also provides for consideration of an arbitrator’s availability and qualifications, including such qualifications that are required by the agreement, and other aspects to ensure such arbitrator’s impartiality and independence.

Dr. Yazdi also shed light on the apparent discrepancy between English, French, and Spanish versions of the ICSID Convention. Considering that all three language versions are equally authoritative, he added, the tribunal in Suez v. Argentina1 held that imposing dual obligations of impartiality and independence was at par with the approach found in many arbitration rules, which require arbitrators to be both independent and impartial.

-

Nationality- He spoke about Article 39 of the ICSID Convention on Nationality of arbitrators, which states that the majority of the arbitrators shall be nationals of States other than the Contracting State party to the dispute and the Contracting State whose national is a party to the dispute. However, the foregoing provisions of this Article shall not apply if the sole arbitrator or each member of the Tribunal has been appointed by agreement of the parties.

-

Grounds for Challenge- Article 57 provides that a party may propose to a Commission or Tribunal the disqualification of any of its members on account of any fact indicating a manifest lack of the qualities required by paragraph (1) of Article 14. Additionally, a party to arbitration proceedings may propose the disqualification of an arbitrator on the ground that he was ineligible for appointment to the Tribunal under Section 2 of Chapter IV.

In this regard, Dr. Yazdi referred to Blue Bank v Venezuela2 wherein the World Bank Chairman applied a lower threshold than previous cases, noting that Articles 57 and 14(1) of the ICSID Convention do not require proof of actual dependence or bias, rather it was sufficient to establish the “appearance of dependence or bias”.

-

Duty of Disclosure- Lastly, he explored ICSID Arbitration Rule 6, under which an arbitrator must disclose facts or circumstances if he or she reasonably believes that such a fact would reasonably cause his or her reliability for independent judgment to be questioned by a reasonable person.

3. IBA Guideline and its applicability to Investment arbitration

On this aspect, Dr. Yazdi spoke about the traffic light system of the International Bar Association (‘IBA’) Guidelines on Conflict of Interest in International Arbitration, 2024. As per this system, there are three categories of relationships that arbitrators can have with the disputing parties and the three degrees of disclosures required to be made by them accordingly.

-

Green list: This category comprises relationships that are unlikely to create doubts about an arbitrator’s impartiality. For example, the disclosure of a previous legal opinion provided to the parties, on an issue that arises in the arbitration, that is not focused on the case, is not required. Dr. Yazdi also shed light on the importance of the question of law in Investment Arbitration and the evolution of International Investment Law by jurisprudence.

-

Orange list: This category comprises relationships that may create doubts about an arbitrator’s impartiality. For example, serving as a counsel for a party previously or having a relationship with other arbitrators or counsels.

-

Red list: This category comprises relationships that will create doubts about an arbitrator’s impartiality. For example, having prior involvement or an interest in the dispute, or having a personal relationship with the parties or counsel.

Thereafter, he explored the topic of Omnipresence of the State wherein he discussed the host State’s concerns on nomination of arbitrator, the question of the Arbitrator’s nationality, the Arbitrator’s relationship with the State-owned/controlled entities and State Academic Institutions and Universities, and professionals serving as occasional or regular advisor to the State or State entities. In this regard, he mentioned the case of Berschader v. Russian Federation3 wherein the appointment of a Russian arbitrator was challenged on the ground that he was a Professor in Moscow College of International Relations (Foreign Ministry College) and serving as an advisor to the Russian Government. This challenge was dismissed by the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce despite being listed in the IBA Red List.

The last issue discussed by Dr. Yazdi was the conundrum between Transparency and Public Interests. He stated that the taxpayers were concerned with the outcome of the investment arbitration, which called for transparency in such disputes. He also spoke about the diversity of public interests and legal standards of independence in Investor-State Dispute Settlement (‘ISDS’).

4. Issue Conflicts:

Concluding his presentation, Dr. Yazdi delved into three of the most common grounds of impartiality and independence in Investment Arbitration, which are as follows:

-

Double Hatting: Double hatting is an individual serving as both the counsel and arbitrator, consequently or concurrently. For example, in Telekom Malaysia Berhad v. Ghana4, Ghana challenged the appointment of a professor who had been appointed as arbitrator by the claimant, because he was simultaneously serving as counsel for the petitioner in the annulment proceedings of RFCCC v. Morocco. The award delivered in that case was being relied upon by Ghana in the present case. Ultimately, it was held that since the professor had to play these two parts, he couldn’t avoid the appearance of not being able to keep these two parts strictly separated. Thus, there were justified doubts about his impartiality if he did not resign as attorney in the RFCC case.

-

Deciding on Similar Legal Issues: Another ground was whether an arbitrator, having once decided an issue of law in a prior case, can be impartial when the same issue is raised in a later case. For example, this question arose in cases relating to BITs between the US and Argentina in CMS Gas Transmission Co. v. Republic of Argentina5 and LG&E Energy Corp. v. Argentine Republic6. Though the two cases arose from nearly identical circumstances and facts, in the CMS case, Argentina’s state of necessity defense was rejected; whereas in the LG&E case, it was accepted.

-

Multiple Appointments: Dr. Yazdi remarked that multiple appointments of an arbitrator by a party or its counsel constituted a consideration that must be carefully considered in the context of a challenge. For example, in the case of Ayat Nizar Raja Sumrain v. State of Kuwait7, wherein the claimants alleged that Prof. Douglas’ multiple appointments by Kuwait and his current service as a State-appointed arbitrator in a related case would cause any reasonable third-party observer to conclude that he manifestly lacked the qualities required by Article 14(1) of the ICSID Convention. The claimants also alleged that another arbitrator, Mr. Veeder, manifestly lacked the qualities required by Article 14(1) because he was appointed as an arbitrator multiple times by Baker & McKenzie LLP (representing the Respondent in this arbitration) in several ICSID cases, and he served with Prof. Douglas on other ICSID tribunals. Both challenges were rejected by the Tribunal.

Cross-Examination in Arbitration

After Dr. Yazdi’s enlightening presentation, Mr. Shashank Garg took the floor to speak on the exercise of cross-examination in an arbitration from an arbitrator’s perspective.

Introducing the topic, Mr. Garg stated that cross-examination was not just a procedural ritual — it could be a sword to test credibility, a shield for fairness, or a circus, if mismanaged.

“You want to be in control of the process; you cannot leave it to the counsels, otherwise the whole exercise of cross-examination can look like a circus.”

– Mr. Shashank Garg, Senior Advocate

He illustrated the role of cross-examination in an arbitral proceeding, which is as follows:

-

It is a tool to test witness credibility and the reliability of evidence.

-

It provides structured fact-finding instead of a mini-trial.

-

It helps arbitrators see beyond written statements, for example, witness demeanour and assumptions.

-

It helps in assessing expert reports for accuracy and reasonableness.

Then, he explained that there were three main characters in the cross-examination:

-

The Witness: The role of the witness is to prove that whatever he has said in the witness statement holds good.

-

The Cross-Examiner: The role of the counsel or the cross-examiner is to impeach or hit on the credibility of the witness and the witness statement.

-

The Arbitrator: The role of the arbitrator is to control the whole process and ascertain the truth.

Reminiscing about the COVID-19 pandemic time when the cross-examinations and hearings started taking place virtually, he mentioned that previously, for a cross-examination or a witness hearing, it was almost certain that even if the tribunal had to fly overseas for several hours, it would happen in person. The reason was that the witness should be in front of the tribunal to see their demeanour, the manner of responding, the confidence in their responses, etc. However, now that virtual hearings have become common, solutions, such as putting three cameras, have been developed.

“The cross-examination, if it has become mandatory or if it is being offered in an arbitration, should give a more detailed and intimate perspective of the evidence to the arbitrator.”

– Mr. Shashank Garg, Senior Advocate

Coming to the aspect of the role of an arbitrator in a cross-examination, Mr. Garg emphasized that it was incumbent upon the arbitrator to set the rules right from the beginning, like whether there would be witness testimonies or whether there was a need for any cross-examination. In this regard, he mentioned the arbitrator-controlled approach suggested in Article 5 of the Rules on the Efficient Conduct of Proceedings in International Arbitration (‘Prague Rules’). It states that the arbitrator can not only decide the order in which the witnesses must present their testimony, but the arbitrator also has the sole right to decide whether cross-examination of a certain witness, one or all, is required or not. Reiterating that rules must be clearly set out, he remarked that in an international arbitration, there could be different cultures. For some cultures, the way common law lawyers do cross-examination could be perceived as very aggressive, for others, it might be very normal.

“What is key here, what is most important here, is that all of these rules must be forthcoming right at the beginning. You don’t want to leave anything to chance. You don’t want to introduce the rules when the cross-examination has already commenced.”

– Mr. Shashank Garg, Senior Advocate

Furthermore, he stated that they must also ensure equal opportunity to the counsels and the witnesses, allow only focused and relevant questioning, and maintain proportionality of the examination in time and scope. On the other hand, they must avoid mini-trials or repetition of prior evidence, fishing expeditions or irrelevant issues, and intimidation or theatrics.

Addressing the procedural order ingredients, Mr. Garg explained that it should have the scope of the cross-examination, sequences of events, expert-handling, document protocol, time limits, objections and rulings, remote versus in-person rules, and admissibility versus weight/ relevance to certain aspects.

Lastly, he reflected on his personal experience as an arbitrator and how he gives leeway in the beginning for counsels to warm up and the first few questions, even if they are superfluous or not so relevant, allowing the counsels to just get in the frame of how they wanted to cross-examine the witness.

AI & Confidentiality: DOs and DON’Ts

Speaking from the vantage point of an arbitrator, Mr. Kirill Laptev delivered a thought-provoking presentation on AI & Confidentiality: DOs and DON’Ts.

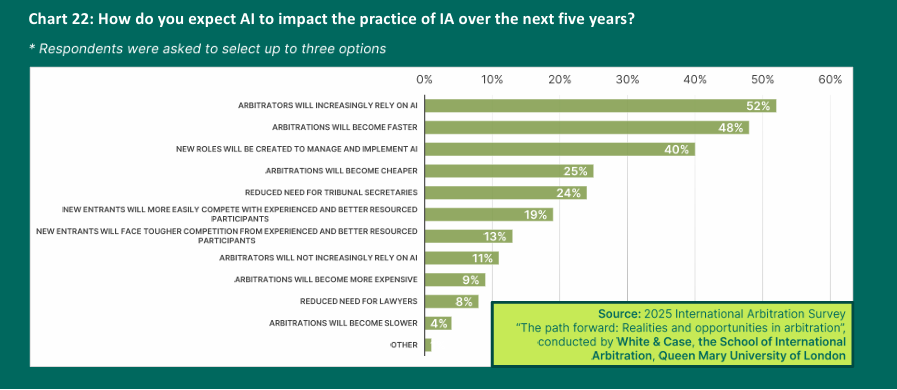

Starting off with the expectations and misconceptions in AI and International Arbitration, Mr. Laptev demonstrated that Parties and Arbitral Tribunals were increasingly using AI for document review, transcripts, drafting, etc., but 47 per cent of the practitioners cited confidentiality risks as the primary obstacle to AI adoption. He emphasized that Tribunals must protect confidentiality while preserving the arbitration procedure and impartiality.

Regarding regulatory regimes, he explored three regimes, which are as follows:

-

General Data Protection Regulation (‘GDPR’): GDPR requires that when processing personal data, controllers and processors observe principles including data minimization, purpose limitation, confidentiality, security, and transparency. If AI tools process personal data of individuals, these rules apply. Arbitration proceedings may straddle borders; if the seat is in Europe or parties/users are in Europe, GDPR obligations impose constraints on what AI services can process, transfer, store, and require vendor contracts, potentially even a Data Protection Impact Assessment (‘DPIA’). He stated that though GDPR does not specifically target AI, many confidentiality/design obligations from GDPR feed into how AI should be used.

-

European Union AI Act: The EU AI Act classifies certain AI systems as “high-risk.” Under Annex III, using AI systems to assist judicial authorities in researching and interpreting facts and the law, or if used in alternative dispute resolution, are considered high-risk systems. This meant stricter obligations, such as risk management systems, technical documentation, human oversight, ensuring robustness, security, and accuracy.

-

CIS Model Law on Artificial Intelligence Technologies: Technologies related to access to data from institutions administering justice (without specific reference to ADR) are classified as AI technologies and/or systems using AI technologies with a high risk (“high-risk”) under Article 21 of the Model Law.

Bringing the focus back to confidentiality issues, Mr. Laptev underscored the three key confidentiality risks in AI use, namely uploading confidential docs to third-party AI (training/retention risks), unintended disclosure via aggregated outputs, searchability, metadata leaks, etc., and cybersecurity exposures through AI integrations or vendors.

Further, he illustrated that an arbitrator had three focus moments in the duration of the arbitration:

-

Pre-hearing: At this stage, the Arbitrator has to ensure that there are disclosures of AI use intentions, a confidentiality risk assessment is undertaken, and procedural fairness is maintained.

-

During the hearing: At this stage, the Arbitrator has to maintain confidentiality through safeguards, manage AI’s impact on evidence and the hearing process, and ensure non-violation of party rights.

-

Drafting the award: At this stage, the Arbitrator has to be transparent about AI’s role, protect confidential material, and preserve arbitral authority.

Delving into the existing confidentiality guidelines, Mr. Laptev explored four types of guidelines for ensuring confidentiality with the use of AI in arbitration:

-

Silicon Valley Arbitration & Mediation Center (SVAMC): The SVAMC Guidelines on the Use of AI in Arbitration (April 2024) provide that all participants must ensure AI use is consistent with obligations to safeguard confidential information (including privileged, private, secret, or otherwise protected data). However, there is no general obligation to disclose alcohol use. When disclosure is appropriate, it should include the AI tool name and version, description of use, and complete prompts with outputs.

-

Stockholm Chamber of Commerce (SCC): The SCC Guide to the Use of AI in Cases Administered under the SCC Rules (October 2024) provides recommendations when AI is used in SCC-administered arbitrations, highlighting that using AI tools may have unintended consequences for the confidentiality of an arbitration. It encourages arbitrators to disclose any use of AI in researching and interpreting facts and the law or applying the law to facts.

-

Vienna International Arbitration Centre (VIAC): The VIAC Note on the use of AI in arbitration proceedings (April 2025) states that arbitrators and parties must respect the confidentiality of the arbitral process as a whole and ensure that AI tools are compliant with any such confidentiality obligations. As per this note, Arbitrators may inform the parties if they plan to use certain AI tools, and parties should be allowed to comment on arbitrators’ AI usage.

-

Chartered Institute of Arbitrators (CIArb): The CIArb Guideline on the Use of AI in Arbitration (March 2025) identifies AI use as posing substantial risks for confidentiality. It provides for mandatory disclosure when AI use may impact evidence, arbitration outcome, or involve the delegation of express duties. Non-disclosure can lead to consequences, such as adverse inferences and cost considerations.

He also shed light on the TIAC Rules 2021 on confidentiality protection, such as Rule 17.4, which provides for the confidentiality of hearings and meetings, including the recordings, transcripts, or documents used in that regard, Rule 32.1, which provides for confidentiality of the award, Schedule 2 which provides for cybersecurity rules and Article 7 which deals with compliance by third parties.

Concluding his presentation, Mr. Laptev provided some key insights from an arbitrator’s perspective. He remarked that Al can assist, but arbitrators must preserve confidentiality, impartiality, and the tribunal’s exclusive decision-making role. Disclosure is essential, not just of AI usage, but of how it’s used, which tool, settings, prompt, human review, vendor, etc. Lastly, he stated that the Arbitral Institutions and rules may catch up as there was a need for clear guidance, model procedural orders, or institutional practice.

“Arbitral Tribunal control + Arbitral Institution attention + early disclosure = biggest protective value.”

– Mr. Kirill Laptev, AL Legal

Effective Advocacy in International Arbitration: What Persuades Arbitrators (and What Backfires)

The last speaker, Ms. Ketti Kvartskhava, provided a thought-provoking presentation on Effective Advocacy in International Arbitration from an Arbitrator’s Perspective. She stated that although no prescription or formula might equally impress every tribunal, some important common rules should be followed.

“When we speak about international arbitration, we tend to focus on the black letter law, the procedural rules, and the substantive issues at stake. But we often find that the manner in which counsels present their case can be just as important as the merits themselves.”

– Ms. Ketti Kvartskhava, Managing Partner, BLC Law Office

She emphasised that effective advocacy in arbitration was not about theatrics or sheer volume, rather it was about being clear, concise, and credible. The understanding of this principle differentiates counsels who help arbitrators reach a well-reasoned award more efficiently from those who often make the process longer, more expensive, and less persuasive to the tribunal.

Ms. Kvartskhava highlighted the following DOs and DON’Ts for a counsel in an arbitral proceeding:

-

The DOs: What Persuades Arbitrators

-

Written Submissions (WS): Starting with the basics, she stated that the WS was the first and most important point of contact of the Arbitrator(s) with the case. The WS must have clear and structured submissions, logically mention the most relevant authorities, precisely put forth the strongest arguments up front, and highlight the most decisive documents/evidence.

-

Oral Advocacy: At the outset, Ms. Kvartskhava emphasised that hearings were for reinforcing the written case, not repeating it. She explained that arguments should be precise, counsels must engage with the questions of the tribunal directly, and possibly use visual aids, like chronologies, diagrams, or slides, to effectively clarify the case and arguments.

-

Witnesses and Experts: She underscored that witnesses are often a decisive element, but only if handled properly. The counsels should prepare witnesses, but not over-coach them, as arbitrators could sense when a witness is reciting a script rather than recounting their experience. They should also help the witnesses focus on the question when they are drawn into speculation or long digressions.

As for experts, she stated that their effectiveness depended on consistency. An expert whose testimony diverges from their report, or who appears to be an advocate in disguise, immediately loses credibility.

-

Professional Conduct: Though professional conduct may not seem like advocacy, Ms. Kvartskhava emphasised that the counsel’s behaviour impacted the proceedings. The counsels should be cooperative and constructive in procedural matters, civil towards their opposing counsel, and demonstrate efficiency by providing practical solutions.

-

-

The DON’Ts: What Backfires with Arbitrators

-

Submissions: The first nail in the coffin, as per Ms. Kvartskhava, was overloading the record by submitting thousands of irrelevant documents, as it weakened the case by diluting the important evidence. Additionally, providing additional or new submissions that repeat the previous arguments instead of complementing or negating them was not appreciated. Repeating the same argument in five different ways also did not make the case stronger; rather, it signalled that the counsel may lack confidence in their own case.

-

Hearings: Regarding this aspect, she warned against being dramatic, evading questions of the tribunal, and overly aggressive questioning in the cross-examination.

-

Ethics and Tactics: The last aspect, as per Ms. Kvartskhava, was maintaining ethics by avoiding tactics like ambushing, i.e., introducing evidence at the last minute, or playing procedural games, over-promising, and re-litigating procedural rulings.

-

In conclusion, she emphasised three words: clarity, credibility, and efficiency, i.e., the Arbitrators value the counsel who help them understand the case, argue with honesty and precision, and respect both the process and the tribunal’s time. She remarked that good advocacy does not guarantee victory, as facts and law still matter. Poor advocacy can obscure even a strong case, while effective advocacy ensures that the tribunal is focused on the merits where they belong.

“Good advocacy helps arbitrators decide the case. Poor advocacy distracts them from it.”

-Ms. Ketti Kvartskhava, Managing Partner, BLC Law Office

1. ICSID Case No. ARB/03/17

2. ICSID Case No. ARB/12/20

3. SCC Case No. 080/2004

4. HA/RK 2004, 788

5. ICSID Case No. ARB/01/8

6. ICSID Case No. ARB/02/1

7. ICSID Case No. ARB/19/20