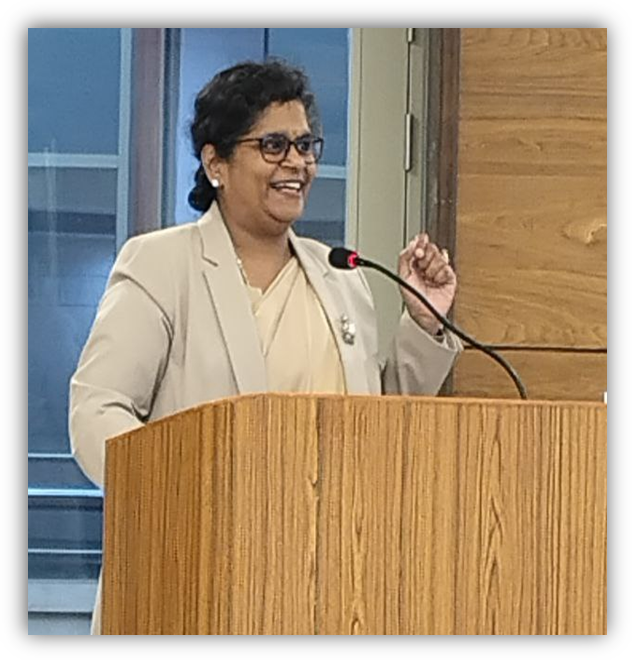

At an enlightening discussion hosted by The Law Forum and EBC on ‘Commercial Disputes Resolution-Challenges and Strategies’, Justice Pratibha M. Singh, Judge, Delhi High Court, delivered a thought-provoking address wherein she spoke about the benefits of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 (‘CC Act’), how its provisions have been and could be used, the changing ecosphere of the commercial disputes arena, and much more.

At the outset, Justice Singh explained how she had witnessed the journey of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 (‘CC Act’), from its creation to its implementation. She mentioned how she appeared before the parliamentary committee to whom the Commercial Courts Bill was referred and had to answer why Commercial Courts (‘CCs’) were required. Explaining the requirement of the At, Justice Singh stated, that it was better to have separate Courts for commercial cases rather than making the regular courts give precedence to such cases.

She remarked that there used to be this mechanism of precedence among cases, but now the system was streamlined with specific courts for specific types of cases without one trampling on another. She also commented that her personal experience with CCs in Delhi in the last 10 years had been good.

Delving into summary judgments, Justice Singh outlined that she received 4 to 5 appellate cases from the CCs every week, and at least 3 of them were Order 13A of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) decrees. She remarked that this was a very good statistic regarding the use of the mechanism of summary judgments. She further explained that in almost all the recovery cases, the defence hardly had a prospect of winning.

She commented that CCs were making a difference at the ground level, as out of the 22,000 commercial suits filed every year in Delhi, 21,500 were disposed of.

Contributing to the discourse on case management, she recounted a matter heard by Justice (Retd.) Hima Kohli. During the determination of jurisdiction, Justice Kohli observed that should the issue be resolved against the defendant- who was insisting on the lack of jurisdiction, then he would be liable to pay Rs. 1 Lakh cost to the plaintiff. This prompt assertion led the defendant to immediately withdraw the objection. Further, she illustrated another Intellectual Property (‘IP’) case, where a list of 80 witnesses was effectively streamlined to 4. By these examples, Justice Singh underscored that such proactive and pragmatic case management is both effective and atypical under the traditional framework of the CPC. She agreed that though the earlier CPC gave power to judges to do such case management, they would get caught up in the quagmire of procedure as they did not have this discretion clearly earmarked. Thus, the experience of judges was completely streamlined into the CC Act.

Thereafter, Justice Singh reminisced upon a personal conversation with Lord Justice Colin Birss, Court of Appeal, United Kingdom, wherein she complained about the difficulties faced by India in dealing with the colonial CPC, and Justice Birss shed light on Section 1 of the UK Civil Procedure Rules which was relied upon by the legal system of UK. Section 1 states that the Court had the power to consider some factors to meet the ends of justice and one of the factors was how much resources the Court a case was going to occupy. She remarked that the UK had moved on much beyond the 117-year-old CPC, and India had to change its CPC as well.

She mentioned that the Delhi High Court (‘DHC’) had taken steps towards this agenda by amending its original side rules. Justice Singh underlined how the Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules, 2018, incorporate principles of the CC Act in the non-commercial litigations, which had helped the commercial division shape non-commercial suits in a very efficient manner. However, the bottleneck was the lack of judges on the original side.

“Using the Commercial Courts Act has been extremely beneficial for commercial litigation.”

Highlighting the benefits of the CC Act, she mentioned that one commercial suit in the Delhi District Courts took less than 2 years for disposal and between 40 to 50 days and 150 to 200 days for execution on average. Thus, in terms of decrees and execution, the CCs were doing extremely well, but Delhi was admittedly a very privileged city and Court.

Regarding the functioning of the IP Division of the DHC, Justice Singh stated, “On an annual basis, the IP Division has more disposals than filings, despite the large number of cases that were transferred from the Intellectual Property Appellate Board to our Court.” She added that 80 percent of the transferred cases have been disposed of in the last 4 years, and the IP division was beating the filling by about 50 matters in a year. She remarked that these statistics showed that having specialised benches, courts, and divisions was helpful and the best way to go forward as a country, considering the increasing commercial disputes in the developing economy. She also highlighted the need for CCs in semi-urban areas or tier 2 cities for the sake of efficiency.

Justice Singh also highlighted how the Karnataka High Court streamlined their original side rules according to the DHC Original Side Rules, the High Courts of Madras, Calcutta, and Himachal Pradesh had proper IP divisions, and most High Courts had IPR, and commercial cases mentioned in their rosters. Thus, the movement for change was happening, but still, as the litigation grows, it would be good to have dedicated divisions and Courts. However, she underscored that with this growth, the strength of judges had to be increased, and more budgetary allocation was required for Courts and their infrastructure.

In conclusion, Justice Singh stated that the provisions of the CC Act could be used in the most efficient manner to make justice dispensation in this area of law extremely efficient.