Part I

Introduction

The build-up of non-performing assets (NPAs) in the banking system over the last two decades has been a major cause for concern for India’s banking-dominated financial sector. This high debt overhang means that a huge amount of investment is tied up in stressed assets, which will continue to deteriorate in quality the longer the debt is not serviced. In 2015, RBI conducted an Asset Quality Review (AQR), instead of the standard Annual Financial Inspection, so that it could examine the quality of assets in the Indian banking system.1

The AQR revealed that many banks were deferring stressed-asset classification. RBI’s inspection forced these institutions to disclose their “bad loans”, causing a jump of around 80% in FY16.2 Though the authorities took steps to address the high NPA ratio, including the introduction of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC/the Code)3 in 2016, many problems still persist. One of these problems is the lack of interest in the actual revival of stressed assets, particularly from Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs). Notwithstanding a dismal rate of recovery (~14.29%), according to a 2021 Report by an RBI Expert Committee, only 20% of the debt recovery made by ARCs resulted from the revival of stressed assets.4

This paper examines whether ARCs have attempted to revive stressed assets or have merely focused on their bottom line. Part II provides an overview of stressed-asset management in India. Part III examines the track record of ARCs vis-à-vis revival-based asset recovery. On the basis of the foregoing discussion, Part IV identifies some difficulties encountered by ARCs in reviving assets and recommends solutions for the same. Part V offers concluding remarks.

Part II

Background

Overview of the Indian asset management framework

NPAs are generally regarded as debt instruments (either loans or bonds) whose obligors are unable to discharge their liabilities as they become due.5 In jurisdictions like the United States, Indonesia, China and India (from FY05 onwards), a stressed asset becomes an NPA when there is non-repayment of the loan or the advance for 90 days or more.6

The Indian stressed-asset management ecosystem encompasses a broad variety of legal mechanisms, one of which is the sale of NPAs to ARCs. Other avenues include Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR), Joint Lenders’ Forum (JLF), Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR), as well as liquidation or resolution under the IBC. This section discusses the history of these stressed-asset management options, with particular emphasis on ARCs.

Examining the succession of laws preceding the introduction of ARCs through the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest (SARFAESI) Act, 20027 sheds light on some features of the Indian ARC model. To begin with, as far back as 1993, the Narasimham Committee I had recommended the establishment of Debt Recovery Tribunals to assist in loan recovery and ease the debt burden.8 Though these tribunals initially witnessed a degree of success, they were (i) bound by a pecuniary ceiling of Rs10 lakhs; and (ii) legally and infrastructurally inadequate to deal with a progressively heavier caseload.9

This may explain why moving forward, the legislature decided to minimise the role of the courts in asset recovery; for example, the SARFAESI Act, 2002 allowed lenders to auction securities without judicial intervention.10 More notably, following the recommendations of the Narasimham Committee II, it also set up an institutional alternative altogether: Section 311 of the SARFAESI Act introduced ARCs to the Indian stressed assets space so that they could “clean” the balance sheets of banks by purchasing NPAs and attempting to profitably securitise and/or restructure them.12

After the introduction of ARCs, however, other asset-management mechanisms were also introduced, ostensibly to deal with different categories of stressed assets. By way of example, the CDR System, 2004 was envisioned by RBI as a way to ensure that the corporate debts of “viable entities” could be restructured in a timely and a transparent way, thus preserving these businesses.13 Similarly, RBI in 2014 issued guidelines on JLFs, directing banks to collectivise and formulate corrective action plans to resolve stressed assets worth Rs100 crores or more within 45 days.14 The year after that, SDR was introduced to allow JLFs and other consortiums of lenders to convert outstanding debts into equity.15

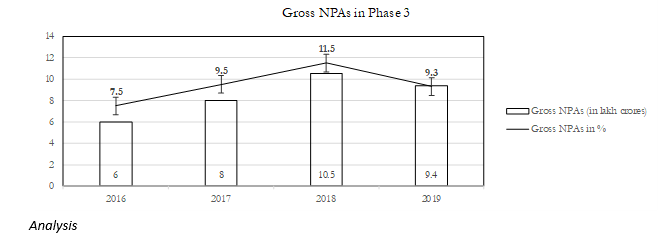

Though these steps were understandable in the context of the rising accumulation of NPAs in the banking system (the gross NPA ratio tripled between FY 2015 and FY 2018)16 these measures also attracted criticism for fragmenting the Indian stressed-asset management regime. As mentioned before, a spike of ~80% in the NPA ratio in FY16 may have impelled the legislature to completely overhaul the existing laws and finally introduce the IBC in 2016.17 Though the IBC prima facie brought in an alternate mechanism, it was never intended to displace ARCs; rather, the broad insolvency framework was expected to assist ARCs in financing the working capital required to revive stressed assets while maintaining profitability.

History of Indian ARC industry

This section discusses the history of the Indian ARC industry, with specific focus on some historical problems that hinder revival of stressed assets today. This history may be divided into three phases: Phase 1, between FY03 and FY13; Phase 2, between FY14 and FY17; and Phase 3, FY18 onwards. These phases primarily only reflect the state of the ARC market and the surrounding regulatory conditions; as an RBI Bulletin pointed out, these trends have usually “… not been synchronous” with the trends in NPAs in the banking sector.18

Phase 1: Between FY03 and FY14

For example, even though the ratio of NPAs in the banking sector was relatively high when ARCs were introduced (hovering around 6% between FY03 and FY06),19 the infancy of the ARC sector meant that not many NPA sales took place. The regulatory environment was similarly underdeveloped, with there being no investment requirement for ARCs.20 An inflection point of sorts came in FY06, with ARCIL acquiring 559 NPAs with a net book value of Rs 21,126 cr.21 From that point on, ARCs began to participate in more asset sales, and the regulatory framework was improved, even as the gross NPA ratio paradoxically dropped to a decade low of 2.6%.22

This low NPA ratio may have done a lasting disservice to the ARC industry. During this time period, banks did not have a particularly compelling motive to clean their balance sheets by removing stressed assets. In 2010, the RBI introduced the 5:95 model (i.e. minimum capital requirement for ARCs to invest 5% of the acquisition value.) Given their healthy economic condition, including the presence of substantial provisioning, banks preferred to offload vintage assets to ARCs, taking a haircut of ~80%.23 Moreover, they also held a large portion of the Security Receipts (SRs), therefore retaining a large part of the risk.24 The ARCs themselves were content to purchase vintage NPAs at steep discounts: the trusteeship fees and low risk assured them of returns if not recovery.

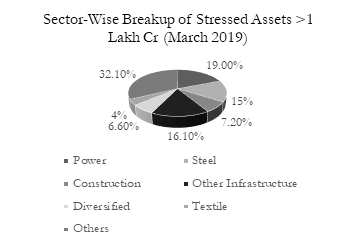

Towards the end of Phase 1, an important change occurred. Apart from a general economic deceleration, the effects of extensive risky lending during the 2000s credit boom began to show. In the preceding years, this credit expansion had coincided with the beginning of a number of capital-intensive infrastructural projects, many of which were public-private partnerships.25

The presence of a government shareholder not only directly translated to fewer leverage constraints, but no doubt also bolstered the confidence of the banks financing these projects, especially public-sector banks, which were at the forefront of this high-risk financing.26 Subsequently, many of these lenders (including Bank of Baroda, IDBI and Punjab National Bank) ended up with a high ratio of NPAs on their bank books (~3% for private lenders and ~4-5% for public sector banks, as of September 2016), while those banks that had not been involved with these infrastructural projects, such as HDFC Bank, were not badly affected.27

Phase 2: Between FY14 and FY17

The infrastructural sector is notorious for inflated initial costs and corporate raiding, both of which make it difficult for lenders to use coercive measures for debt recovery, at least without significant haircuts. Given the immense economic and developmental importance of the infrastructural sector, the authorities intervened to encourage ARCs to participate in the clean-up. A 2014 RBI Circular expressly stated that ARCs were to function as a “supportive system for stressed-asset management” in order to enable “asset reconstruction, rather than asset stripping”.28 It further stressed that NPAs had to be sold when there was a fair chance of debt recovery.29

Consequently, there was a large amount of asset sales: according to one estimate, 40% of asset sales to ARCs (in terms of net book value) occurred between July 2013 and August 2014.30 This increased regulatory scrutiny of ARCs, particularly of risk retention by banks through subscription to SRs.31 Another notable feature of Phase 2 was that because ARCs could comfortably rely on trusteeship fees for the earnings (particularly after a one-time investment of only 5%), they were not incentivised to stringently pursue recovery, particularly through revival.32

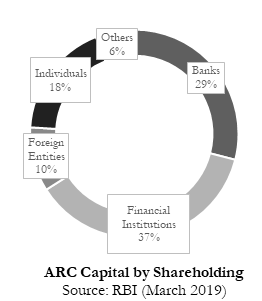

RBI responded by making several significant changes. The investment requirement was raised to 15%, and the trusteeship fees was now to be calculated as a percentage of the Net Asset Value (NAV), as opposed to on the basis of the volume of outstanding SRs.33 Foreign investors were also allowed to become “sponsors” of ARCs.34 All of this was meant, at least in part, to encourage ARCs to recover more, particularly through revival-oriented methods.35

Phase 3: FY17 onwards

However, with the introduction of the IBC in 2016, ARCs quickly lost traction as an asset-management mechanism. RBI tried to provide an impetus to ARCs by once again altering their business model, most notably by raising the provisioning requirement for banks.36

Source: RBI & CRISIL

This brief history of ARCs in India highlights three key features of the Indian ARC model, which also distinguish them from foreign ARCs (which are more popularly known as Asset Management Companies, or “AMCs”).

First, ARCs were not recognised in India as a response to a financial crisis. Rather, they were a logical step after the underperformance of the preceding statutory asset-management mechanisms. This is different from countries like Sweden or Germany, where AMCs were introduced a response to the 2008 global financial crisis, or even from other Asian countries (including Indonesia, Korea, Japan, and Thailand), where AMCs were brought in after the Asian financial crisis.37

Second, because of the abovementioned reason, Indian ARCs are not bound by sunset clauses. According to the World Bank, a sunset clause of between 5 and 15 years allows ARCs to “focus [on their] mandate” and prevent “mission creep”.38 Though Indian ARCs also have 5 years for asset resolution39 such a time period (i) is very different from a sunset clause, which dictates the entire existence of the ARC; and (ii) may be extended up to 8 years after acquiring their Board’s approval.40 The concomitant delays may be part of the reason creditors opt for time-bound recovery through other avenues, such as the IBC.

Third, and most importantly, India elected a private sector model for ARCs. It is uncommon for ARCs to receive no funds from the public purse — usually, there is Government involvement, such as through setting up of State-owned ARCs (Sweden, Malaysia and Ghana), public-private partnerships (Spain and Ireland), or at least significant financing from the Government (South Korea and Thailand.)41 As the paper later discusses, this makes profitability a major consideration for ARCs, incentivising them to prioritise their returns over reviving assets.

Part III

Why ARCs have focused on returns, not revival

After isolating and acquiring the “bad loan,” the ARC may liquidate it, treat it as a “going concern”, or adopt some combination of both approaches, depending on the nature and viability of the asset. As per RBI Guidelines issued under Section 9(2)42 of the SARFAESI Act, the following measures are used for asset resolution:

|

Resolution Method |

Per cent of Total Assets Resolved |

||||

|

March 2016 |

March 2017 |

March 2018 |

March 2019 |

March 2020 |

|

|

Rescheduling of payment obligations |

37 |

36.5 |

36.8 |

35.7 |

32 |

|

Enforcement of security interest |

32 |

35.1 |

31.5 |

28.6 |

26.6 |

|

Settlement of borrower’s dues |

30.0 |

24.8 |

25.2 |

28.4 |

26 |

|

Change in or takeover of management of the borrower’s business |

2.0 |

3.9 |

6.2 |

7.2 |

1.5 |

|

Sale or lease of borrower’s business |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

13.9 |

Source: RBI Bulletin (April 2021)

These figures demonstrate that even liquidation aside ARCs prefer to resolve assets by simply rescheduling the debts payable by the borrower. There is a consistently low focus on change in/takeover of management and assets. However, this is not entirely attributable to the ARCs themselves.

ARCs were only presented with the option to recover debts through reviving stressed assets in 201043, and were required to restore control of the business to the borrower afterwards. Similarly, the possibility of converting part of the borrowers’ debt into equity also came about as late as 2014, subject to the ARC shareholding being not more than 26% of the post-converted equities.44 There have been a number of other regulatory changes, which, though less significant, have affected the ability of ARCs to keep step with the legal requirements. Other difficulties may include:

|

Execution Difficulties |

Inter-Creditor Conflict |

Legal Problems |

||

|

difficulty in raising capital |

differences with respect to course of revival |

long delays due to large caseload |

||

|

lack of judicial expertise |

||||

|

irregular regulatory landscape |

||||

|

small capital base |

lack of adequate funding |

lack of understanding |

fear of punitive consequences |

|

|

borrower’s management being uncooperative |

uncertainty about size of deal offered |

|||

|

retaining promoters’ support |

||||

Part IV

Problems and solutions

The 2021 RBI Report highlighted the ARC sector’s consistent underperformance, including a poor recovery rate, low upside, small capital base and a lackluster track record insofar the revival of stressed assets is concerned.45 With respect to the last element, the Report pinpointed a lack of focus on revival-based recovery and inadequate skillset for a “holistic resolution” of stressed assets.46 This section identifies the major difficulties ARCs encounter while reviving NPAs, and offers solutions for the same.

Nature of NPAs sold

A major problem lies not with the ARCs, but the banks that sell NPAs to them. As discussed above, ARCs have often been regarded as a “last resort” for banks to dump vintage assets, many times to postpone provisioning. Even if banks want to sell recent/low-vintage stressed assets to ARCs, the requirement to book the shortfall right away may deter them from doing so. Of the few assets that ARCs purchase, therefore, most are aged and unviable. Despite this, ARCs have sometimes tried to revive NPAs; for example, after the failure of the CDR exercise, Edelweiss had bought over 60% Bharati Shipyard’s loans (worth Rs 8500 crores) and attempted to deploy some revival measures.47

To begin with, financial institutions must identify and list stressed assets that can be sold to ARCs. As per recommendations given by the RBI in 2016, this listing of “doubtful” assets should preferably include the specific assets to be sold, details of the sale, accurate valuation (so that the realisable value of the asset is presented to potential buyers) and so on.48 ARCs will modify their bidding strategies to purchase low vintage assets only when there is a strong possibility of recovery, as well as when stressed assets are backed by capital such as machinery and land.

On the regulatory front, this may be addressed through enhanced amortisation. Though RBI had earlier allowed lenders to spread the loss on asset sales on an ad hoc basis,49 there are no current mechanisms in place for dispensation of the shortfall.

Lack of debt aggregation

One of the major anticipated advantages of ARCs over other debt recovery avenues is debt aggregation. After acquiring NPAs, ARCs are expected to hold them in debt portfolios. This is beneficial because (i) collecting multiple claims in one place enables better negotiation with the debtors, particularly when the debtor is better positioned than the individual claim holder; and (ii) investors may prefer to buy larger quantities of stressed assets and/or deal with a single seller i.e. the ARC.

In order to build a versatile and attractive debt portfolio, under Section 550 of the SARFAESI Act, ARCs can be permitted to acquire “financial assets” from a wider range of institutions, including non-domestic banks/financial institutions, alternative investment funds (AIFs), and even other ARCs/AMCs.

Moreover, to minimise inter-creditor conflict and to harmonise the ARC framework with the IBC, the creditor consensus required to affect an asset sale to an ARC can be lowered from 75% to 66%.

Inadequate capital base

The revival of stressed assets is highly capital intensive. Though the ARCs are not the only avenue to resolve stressed assets, according to one estimate, even the combined capitalisation of every ARC in the market (~Rs 3k crores) was dwarfed by amount of stressed assets in the banking system (~Rs 654.1k crores.)51 This is a serious mismatch, which cannot be remedied by infusing capital on a one-time basis. There must be a consistent capital flow in order for ARCs to be able to revive businesses.

The current minimum prescription for net owned fund (NOF) is a mere Rs 100 crores. Accordingly, the majority of ARCs (75%) have an NOF level between Rs 100 and Rs 200 crores, even though the top 10% of ARCs have NOF level above Rs 1500 crores.52 More generally, 62% of the industry’s capital base is held by the Top 5 ARCs.53 Of the twenty-eight players in the ARC market, then, most are uncompetitive and lack the capacity to effectively resolve assets. One way this may be corrected is by raising the NOC level: an RBI Expert Committee in 2021 recommended raising it to Rs 200 crores.54

Capital shortage can also be addressed by bringing in new ways to expand the non-NOF capital base. Currently, ARCs also rely heavily on domestic banks and financial institutions for funding (the figures are usually comparable to the NOF). This is particularly worrying as the same banks may both sell and lend to ARCs in order to move their funds. In order to diversify capital-raising avenues, other sources such as individual investors, corporates, trusts, funds etc. can be permitted to lend to ARCs. Further, Section 2(1)(zh)55 of the SARFAESI Act can be amended to raise the threshold of a sponsor’s shareholding from 10% to 20% so that both the ARC and the sponsor are duly invested in the operations of the ARC.

Lack of expertise

Even if ARCs have the requisite capital to turn-around borrowers, they must have the skill set in order to do the same. In the past, ARCs have failed to leverage their comparative advantage over the lender who sell NPAs: as per the IMF, ARCs can bring a unique expertise and enhanced capacity to the process.56 For example, due to a lack of history between the ARC and the borrower, the ARC can be more objective and stringent about the recovery.

One of the major functions that ARCs can discharge that also assists in recovery is accurate valuation of stressed assets. Experts forecast that the volume of NPAs in the banking system may be inflated, and ARCs can professionally estimate the actual value of these assets before purchasing them.

Changing the management fees model

One serious concern even the 2021 RBI Expert Committee Report overlooks is the trusteeship-fee model. As the paper discusses above, the fees were first linked to outstanding volume of SRs and are now linked to the NAV at the lower end of the net value specified by the credit rating agency (CRAs). This is to motivate ARCs to focus on recovery, as a drop in the recovery rating directly diminishes their earnings. However, this new value of SRs is not always accurate.

The fees can be directly linked to the recovery, instead of circuitously through the SR value. Not only is determination by CRAs expensive, it is also based on its own estimations, which may be distorted. Combined by the fact that ARCs may even spread or protract recovery (as witnessed in Phase II) in order to earn from fees, it may be preferable to change the model and incentivise recovery in fresh ways.

SRs can also be converted into unsecured debts which are “discovered” during the bidding process, as this will promote realistic valuation.

Interface with other mechanisms

Lastly, the interface between ARC operations and other stressed-asset management mechanisms must also be improved so the laws can supplement, not contradict each other. There have been some steps taken towards this goal: for example, RBI in October 2022 allowed ARCs to act as resolution applicants under IBC.

To minimise friction between creditors and ARCs, the time period for asset resolution must be consistent with the plan supplied by the lenders’ consortium.

Part V

Conclusion

Despite some improvement in the recent years, India’s debt problem continues to slow economic development, particularly by constraining fresh lending. Over twenty years after their inception, it has become apparent that the Indian ARC model has some inherent weaknesses — but in the presence of a strong asset-management ecosystem (particularly after the promulgation of the IBC), ARCs can now embrace their status as special purpose vehicles to cull out viable stressed assets and effectively revive them. To this end, this paper makes a number of recommendations on both the company and the regulatory side.

†5th year student at National Academy of Legal Research and Studies (NALSAR). Author can be reached at natasha.singh@nalsar.ac.in.

1. N.S. Vishwanathan “Asset Quality of Indian Banks: Way Forward” (RBI Bulletin, October2016).

2. N.S. Vishwanathan, “Asset Quality of Indian Banks: Way Forward” (RBI Bulletin, October2016).

3. Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016.

4. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

5. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (March 2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

6. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (April 2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4. See also David Bholat et al., “Non-Performing Loans: Regulatory and Accounting Treatments of Assets”, Bank of England (May 2016).

7. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Securities Interest Act, 2002.

8. Amarnath Yadav and Pallavi Chava, “ARCs in India: A Study of their Business Operations and Role in NPA Resolution” (RBI Bulletin, April2021)

9. Amarnath Yadav and Pallavi Chava, “ARCs in India: A Study of their Business Operations and Role in NPA Resolution” (RBI Bulletin, April2021).

10. Amarnath Yadav and Pallavi Chava, “ARCs in India: A Study of their Business Operations and Role in NPA Resolution” (RBI Bulletin, April2021).

11. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, S. 3.

12. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

13. K.C. Chakrabarty, Dy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, address at the Corporate Debt Restructuring Conference 2012: Corporate Debt Restructuring — Issues and Way (11-8-2012).

14. Dixit Yadav, “Evolution of the Resolution Framework for NPAs in India: A Study of Assets Reconstruction Companies and Bad Bank Proposal”, Business Analyst ISSN 0973 – 211X, Vol. 42(1), 141-163.

15. Dixit Yadav, “Evolution of the Resolution Framework for NPAs in India: A Study of Assets Reconstruction Companies and Bad Bank Proposal”, Business Analyst ISSN 0973 – 211X, Vol. 42(1), 141-163.

16. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

17. Dixit Yadav, “Evolution of the Resolution Framework for NPAs in India: A Study of Assets Reconstruction Companies and Bad Bank Proposal”, Business Analyst ISSN 0973 – 211X, Vol. 42(1), 141-163.

18. Amarnath Yadav and Pallavi Chava, “ARCs in India: A Study of their Business Operations and Role in NPA Resolution” (RBI Bulletin, April2021)

19. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

20. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

21. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

22. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

23. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

24. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs : Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

25. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

26. N.S. Vishwanathan, “Asset Quality of Indian Banks: Way Forward” (RBI Bulletin, October2016).

27. N.S. Vishwanathan, “Asset Quality of Indian Banks: Way Forward” (RBI Bulletin, October 2016).

28. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

29. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

30. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

31. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

32. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

33. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

34. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

35. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

36. Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) and Credit Rating Information Services of India (CRISIL), Bolstering ARCs: Focus on Quicker Resolutions and Co-investor Model Among Imperatives (August 2019).

37. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

38. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

39. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

40. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

41. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

42. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, S. 9(2).

43. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

44. Jaimini Bhagwati, M. Shuheb Khan and Ramakrishna Reddy Bogathi, “Can Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) be Part Solution to the Indian Debt Problem?” (2017) Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations 4.

45. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

46. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

47. “Edelweiss Gets Helping Hand from PMO on Bharati Shipyard’s Revival” (The Economic Times, 24-10-2015).

48. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

49. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

50. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, S. 5.

51. Asset Reconstruction Companies: Small Steps on a Long Road Ahead (Alvarez & Marsal 2014).

52. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

53. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

54. Reserve Bank of India, Report of the Committee to Review the Working of Asset Reconstruction Companies, 14, para A.9 (September 2021).

55. Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002, S. 2(1)(zh).

56. David Woo, “Two Approaches to Resolving Non-Performing Assets During Financial Crisis” (2000) IMF Working Paper 3.

I appreciate the insightful article on “Profit with Purpose: Have ARCs Focused on Returns or Revival?” This piece provides a thought-provoking analysis of the role of Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs) in balancing financial returns and the revival of distressed assets. It sheds light on the critical dilemma faced by ARCs and the potential impact on the broader financial ecosystem. Well-researched and thoughtfully presented, this article is a valuable resource for anyone interested in the intersection of finance and social responsibility.