“There must be a law in existence to justify an encroachment on privacy. Such a law should have a legitimate objective and rationale behind it. It must conform to the constitutional mandate and pass muster of proportionality test.”-

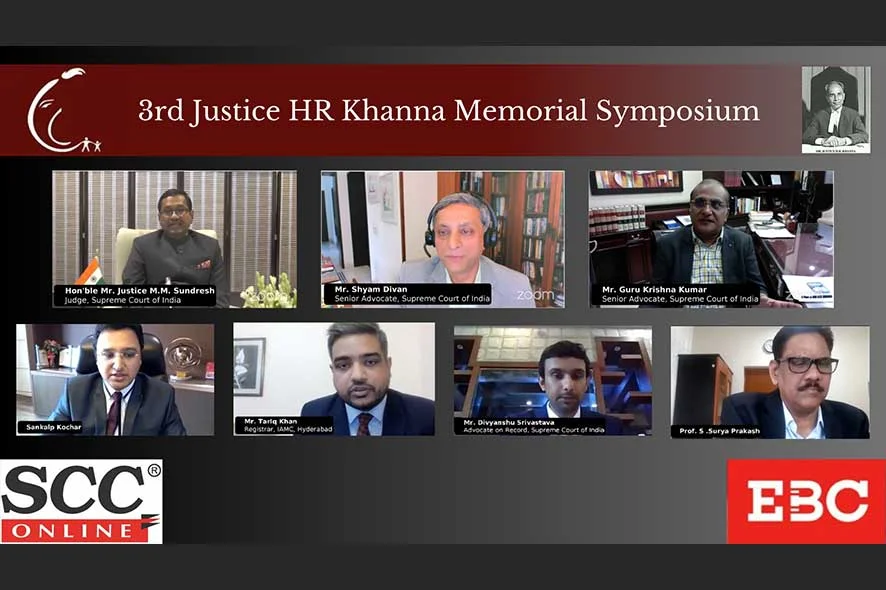

Justice MM Sundresh at ‘3rd Justice HR Khanna

Memorial National Symposium’

National Law Institute University, Bhopal, Hidayatullah National Law University, Raipur and CAN Foundation hosted the ‘3rd Justice HR Khanna Memorial National Symposium’ on July 8, 2023. The Symposium commemorated Justice HR Khanna’s legacy and witnessed discussion in two enthralling sessions bracketed by a break. The Pre-Lunch Session on the theme “State Surveillance & Privacy: The Lakshaman Rekha Between”.

The Pre-Lunch Session was graced by the presence of Justice MM Sundresh (Judge, Supreme Court of India), who was the Chief Guest at the Symposium, and also saw the erudite contributions of Mr. S Guru Krishnakumar and Mr. Shyam Divan (Senior Advocates, Supreme Court of India).

The session was moderated by a panel of young and upcoming lawyers of the nation and comprised Mr. Sankalp Kochar (Adv., MPHC), Mr. Abhikalp Pratap Singh (AOR, SCI), Mr. Tariq Khan (Registrar, IAMC, Hyderabad), and Mr. Divyanshu Srivastava (AOR, SCI).

The welcome address was delivered by Prof. (Dr.) S. Surya Prakash, Vice Chancellor, National Law Institute University, Bhopal (NLIU). Justice Sundresh highlighted that the topic of the session resonated with the principles advocated by Justice Khanna:

“The topic is an ever-relevant one, in the backdrop of the lofty ideals of expounded by Justice HR Khanna.”

To set the stage for this important discussion, Justice Sundresh drew inspiration from a quote from George Orwell:

“It was terribly dangerous to let your thoughts wander when you were in any public place or within range of a telescreen. The smallest thing could give you away. A nervous tic, an unconscious look of anxiety, a habit of muttering to yourself – anything that carried with it the suggestion of abnormality, of having something to hide. In any case, to wear an improper expression on your face (to look incredulous when a victory was announced, for example) was itself a punishable offence.”

Continuing onto the topic of discussion, Justice Sundresh traced the origins of surveillance back to ancient civilizations, demonstrating that the concept was as old as civilization itself. He highlighted that historical accounts are abundant with instances where states had employed surveillance as a mechanism to assert control and safeguard themselves against external threats. He pointed out that even in ancient texts like Dharmashastras and Hitopadesha,the importance of privacy was recognised and it was considered as an inherent aspect of human nature.

After drawing from historical accounts, he shed light on the evolution of surveillance in the context of technological advancements. He emphasized that the invention of telegrams, telephones, and electronic communication opened up new arenas for surveillance, enabling authorities to intercept and tap into messages. He also highlighted that surveillance technology played an integral role in criminal investigations by aiding in the identification and apprehension of the offenders of the law. He underscored the need to strike a delicate balance between effective investigation and the protection of individual privacy. He quoted Judge Louis Brandis of the Supreme Court of the United States:

“The intensity and complexity of modern life and advancing civilisation, have rendered necessary some retreat from the world, and man, under the refining influence of culture, has become more sensitive to publicity, so that solitude and privacy have become more essential to the individual; but modern enterprise and invention have, through invasions upon his privacy, subjected him to mental pain and distress, far greater than could be inflicted by mere bodily injury.”

Justice Sundresh underscored the significance of the Supreme Court’s ruling in K.S. Puttaswamy, which recognized privacy as a Fundamental Right protected under Article 21 of the Constitution. He emphasized the progressive nature of this decision, highlighting the constitutional imperative to safeguard and uphold privacy. However, he also noted that there was great importance in establishing a robust legal framework to determine the justifiability of any encroachment on privacy.

According to Justice Sundresh, such infringements should be subject to existing legal tests, ensuring that they are legitimate, aligned with constitutional requirements, and pass the test of proportionality. In support of his stance, he referred to the seminal judgment of the K.S. Puttaswamy case, which made noteworthy observations on this matter:

“Now, would this Court in interpreting the Constitution freeze the content of constitutional guarantees and provisions to what the Founding Fathers perceived? … The vision of the Founding Fathers was enriched by the histories of suffering of those who suffered oppression and a violation of dignity both here and elsewhere. Yet, it would be difficult to dispute that many of the problems which contemporary societies face would not have been present to the minds of the most perspicacious draftsmen. …as society evolves, so must constitutional doctrine. The institutions which the Constitution has created must adapt flexibly to meet the challenges in a rapidly growing knowledge economy…”

He added that after the Puttaswamy I and II judgements, it becomes the responsibility of the state to recognize and uphold this right, and restrictions could only be imposed when they meet the criteria of proportionality and align with Constitutional principles.

Justice Sundresh noted that while privacy has been recognised to be a Fundamental Right, it is not unfettered, as it is still bound by the limitations under the law. He highlighted that there is a peaceful co-existence between surveillance and privacy. He emphasized that surveillance is a necessary aspect of modern society. He added:

“The modern world has become a difficult place to live and to maintain peace. The cost of peace is high. Any state which lacks expert surveillance would be considered weak. It is both externally and internally vulnerable. While agreeing that surveillance has become a part of governance, the concern is with respect to its exercise, particularly in cases involving one’s own citizens.”

He further stressed that surveillance plays a key role in criminal investigations and can target different individuals. The main objective of surveillance at the end of the day is to identify and apprehend perpetrators. However, it is crucial to use surveillance appropriately and avoid excessively intrusive methods such as phone tapping, email interception, and GPS tracking which are commonly employed. He cautioned that with the widespread use of mobile phones, these techniques have become more accessible and advanced. He took the example of a cinematic movie which was released 25 years ago, “Enemy of the State”:

“To trace an alleged fugitive on the run in the movie, the agencies employed voice recognition technology on a call the said fugitive made from a public phone booth in a different state within the United States. Satellite technology was also used to locate the public phone, along with the CCTV cameras.”

Continuing his speech, Justice Sundresh emphasized the importance of digital devices in investigating white-collar crimes, citing the example of Max Schmidt, a teenager from Germany who utilized the internet to run a multimillion-dollar drug business. He said that these instances highlight the evolving sophistication of technology-driven offences and the crucial role played by digital evidence in criminal investigations. Justice Sundresh’s insights highlighted the need for adapting legal systems to keep pace with technological advancements and address emerging challenges in the digital age.

He acknowledged the implications of artificial intelligence and machine learning, mentioning both, the benefits and drawbacks associated with these advancements. Commenting upon the ground reality of increasing surveillance, Justice Sundresh cited the case of Puttaswamy, in which the Supreme Court has cautioned:

“We are in an information age. With the growth and development of technology, more information is now easily available. The information explosion has manifold advantages but also some disadvantages. The access to information, which an individual may not want to give, needs the protection of privacy. The right to privacy is claimed qua the State and non-State actors. Recognition and enforcement of claims qua non-State actors may require legislative intervention by the State.”

He concluded his address by adding that it is essential to have a codified law that authorizes surveillance actions by investigating agencies while upholding the Constitutional mandate and preserving individual privacy. Recognizing the challenge faced by the courts, he emphasized the need to define the boundaries of privacy while facilitating criminal investigations, requiring a delicate balance. In conclusion, he said:

“The duty to preserve privacy as a cherished right is enjoined by the Constitution on all three pillars of democracy meant to be given effect through the prism of proportionality which would go a long way in the effort of nation building. The task is very complex but it is interesting to note that it would continue to haunt the courts very frequently in the coming years.”

Address by Sr. Advocate Mr. Gurukrishnakumar-

In his captivating speech, Mr. S Guru Krishnakumar highlighted the irony of our times with a thought-provoking story. He said that the initial celebration of remarkable technological advancements turned sombre when it became evident that progress without direction is a pressing dilemma in the modern era, particularly with significant advancements in Artificial Intelligence.

Mr. Krishnakumar drew attention to a news article highlighting the impact of uncontrollable AI on privacy. He remarked,

“Technological development on one hand is fantastic, and the effect on privacy is mind-boggling.”

The focal point of the speech was the questioning of the state’s involvement in surveillance. Mr. Krishnakumar presented the state’s interests, such as crime prevention, counterterrorism efforts, and maintaining law and order, as justifications for surveillance. He referred to an article in the Harvard Law Journal that discussed the historical perspective on the subject of surveillance citing philosophers like Immanuel Kant and Hobbes. According to Kant, spying activities by rulers were immoral, while Hobbes believed intelligence gathering was a core responsibility of the rulers.

With this background, Mr. Krishnakumar continued on to refer to landmark judgments of the Supreme Court on privacy, which included the Puttaswamy judgment, and PUCL judgment, which recognized ‘Privacy’ as a Fundamental Right. He highlighted the Court’s establishment of guidelines for phone tapping, requiring it to be fair and reasonable. These guidelines were later incorporated into the Indian Telegraph Rules. The criteria laid down in the Puttaswamy case, such as the necessity of a legal framework, the legitimacy and justification of incursions into individual rights, and the proportionality of measures taken, were thoroughly examined.

“The three criteria that were laid down in Justice Chandrachud’s decision are as follows: There must be a law to back any kind of incursion into individual rights. The need to have legitimacy and justification for that, i.e., to say there is some larger public purpose or object which is sought to be achieved with the incursion which is sought to be done. Importantly, the nature of the measure being taken must be consistent with the object, whether it is proportionate or disproportionate with the object that is sought to be achieved….. Justice Kaul has also paraphrased this standard with one additional factor, namely, the need for procedural safeguards in respect of whatever be the measures.”

According to Mr. Krishnakumar:

“there needs to be some kind of judicial oversight when considering the concentration of power in the executive. He emphasized the importance of ensuring that decisions on surveillance are justified and constitutionally sound, stating, “If it is going to be exclusively and entirely in the hands of the executive, I would think that it may not stand the scrutiny of proportionality.”

Referring to the Pegasus Snooping case, Mr. Krishnakumar highlighted the need for judicial scrutiny, stating,

“We are in a situation where we have a surveillance regime and we do not have any kind of judicial scrutiny.” He stressed the importance of drawing a line and establishing limits on state power, suggesting that “Is there some kind of Laxman Rekha which needs to be drawn?”

Regarding the proposed Personal Data Protection Bill, Mr. Krishnakumar expressed concerns about its limited applicability to the state. He pointed out that this provision would allow the state to collect and use data without the same protections as other entities, questioning the constitutionality of the proposed regime. He stated,

“That raises a very very significant question on the validity and constitutionality of the regime that we are looking at.”

He emphasized the issue of cybercrime and highlighted the need for a robust data protection regime. He stated,

“We finally have a bill for data protection… The problem is the draft bill proposes that it will not apply to the state which means we go to the basic point that the state would be able to collect data and use it in the manner it seeks to do.”

On State’s exemption from the PDP Bill, he further went on to ask

“So a question would arise whether there is some kind of regime from Caesar to Caesar.”

In conclusion, Mr. Krishnakumar flagged these issues for further consideration, stressing the importance of balancing the right to privacy with the public interest of crime detection and prevention.

Address by Sr. Advocate Mr. Shyam Divan-

Following that, Mr. Shyam Divan (Senior Advocate, Supreme Court) shared his thoughts on the topic with the audience. He initiated his address by fondly reminiscing about a cherished childhood memory of his when he had the privilege of briefly meeting Justice Khanna during a special celebration honouring his father’s remarkable 50 years of practice at the Bar. Mr. Divan expressed his admiration for Justice Khanna’s courage and highlighted his significant contribution to the legal field by introducing the concept of the ‘Basic Structure Doctrine’.

Expressing his heartfelt gratitude, Mr Divan thanked the CAN Foundation for their commendable organization of the event. He expressed his appreciation for their choice of a relevant theme for the Symposium, emphasizing the paramount importance of privacy in protecting an individual’s freedom. Mr. Divan further emphasized that this theme resonated deeply with the values espoused by Justice HR Khanna, underscoring the integral role privacy plays in upholding the rights and liberties of individuals.

Mr Divan recalled the writings of the esteemed Nani Palkhivala during the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case:

“6 judges decided the case in favour of citizens and 6 in favour of the state. Justice HR Khanna agreed with none of these 12 judges and decided the case midway between the two conflicting rights. Thus, by a strange quirk of fate, the judgement of Justice Khanna with which none of the other judges totally agreed has become the law of the land.”

In his speech, Mr. Divan shared his pearls of wisdom on the topic by referencing the insights of American author Shoshana Zuboff, who coined the term ‘Surveillance Capitalism‘ to describe the current era. Mr. Divan emphasized the importance of addressing this phenomenon and its implications for society. He then outlined fourcardinal principles that he believed were essential for preserving an open society and fostering inclusivity.

Firstly, he emphasized the importance of establishing durable legal principles for surveillance to ensure clear guidelines and safeguards for protecting individual rights and privacy.

Secondly, he urged courts to exercise courage and periodically assess the impact and implications of surveillance technologies, setting clear boundaries for the state and technology companies by saying, “this far and no further.”

Thirdly, Mr. Divan emphasized the “fragility of freedom”, noting that it diminishes and disappears rapidly if not protected.

Fourthly, he underscored the significance of a constitutional framework grounded in peaceful contestations and a healthy distrust of state power. He said that by avoiding overreliance on the state in judicial processes, societies can avoid the constriction of freedom and liberty.

During his speech, Mr. Shyam Divan referenced the movie “The Truman Show” to illustrate the consequences of pervasive surveillance. He highlighted the storyline wherein the main character discovers that his entire life has been under constant surveillance since his childhood and this realization comes at a great personal cost to Truman, as he grapples with the loss of privacy and autonomy. Mr. Divan used this example to emphasize the importance of safeguarding individuals’ rights to privacy and the potential harm that can arise from unchecked surveillance. By invoking this thought-provoking film, he underscored the need for robust legal and ethical frameworks to protect individuals from intrusive surveillance practices.

In his concluding remarks, Mr. Shyam Divan emphasized the immense power wielded by surveillance technologies and artificial intelligence. He expressed concern over the lack of transparency surrounding surveillance companies and the vast amount of data they possess on individuals. Mr. Divan cautioned that if unchecked, such technologies could render the state and its citizens powerless, with the potential for dire consequences. He underscored the negative impact such technologies could have on an individual’s freedom and confidence. As the lead counsel in the Aadhaar case, Mr. Divan shouldered the responsibility by saying:

“one of the points which I thought will not require too much efforts to persuade the Supreme Court but we failed on it. I thought before the judgment came that the biometrics…my fingerprints were mine, that was the impression I was under… the argument was that my fingerprints are mine and I must’ve custody, control and commune over them….it cannot be taken away by the government…even if it is taken away then it should be completely under my control…this was the argument with which we tried to persuade the Supreme Court, we were unfortunately rejected.”

The Entire Session can be viewed at:

SCC-EBC group were the Knowledge Partners of the event with Bar and Bench as the Media Partner.