It is common for high praise and tribute to follow the passing away of anyone. Often, the image that is created is larger than life, and flawless. Such hagiography, while bringing a measure of comfort to the bereaved, does disservice to a life that was lived in full measure. It would be expected then that what follows would be a wart-ridden account of a man. It probably would have been, had that man not been M.N. Krishnamani.

For those who have been privy to the video of MNK speaking from his hospital bed a few days before his demise, his stoic acknowledgment of his impending fate and the dignity of his demeanour reflected him in full measure. He would not have been blamed for tears, or an uncharitable word. But he had none. His life, he said, had been a full one without regrets, and he was confident that he had never committed a bad deed. Childlike it may be, but such a sentiment showed the simplicity with which he viewed life till the end.

At least three versions of MNK’s biodata would be read out in his Full Court Reference, and I will therefore avoid talking about when he graduated and when he was designated, not least because these would have been irrelevant to him. Uniformly courteous, good-natured and compassionate, MNK’s lasting impression at the Supreme Court Bar (which he presided over many times) would be of one who was always available to help a person in need. He made it a point to raise funds and donations for those advocates and their families who were in dire need because of a health or family crisis. He literally harangued the well-heeled seniors to part with donations and to accommodate youngsters looking for chambers. He was always eager to take up pro bono causes, especially those concerning the indigent and the exploited.

Universally, to those who knew him earliest from the chambers of M.K. Nambyar and later K.K. Venugopal, he was regarded as a spiritual savant. Rohinton Nariman referred to him often as a “saint”. To P. Chidambaram, he was a “very good man”. Even his senior, K.K. Venugopal referred to him as “my guru”, showing how those older to him would consider MNK a moral compass.

For many years, the leaders of the Madras Bar had avoided shifting to practise in the capital, partly due to the cultural gulf and partly due to the uncertainty that such a move wrought. Venugopal was the first, a few years after his designation by the Supreme Court, and with him, C.S. Vaidyanathan. Encouraged by their success, M.N. Krishnamani followed his chamber mates, and in his wake the two Attorney Generals — K. Parasaran and G. Ramaswamy. Now, with hundreds of young lawyers not only from Chennai but across this great nation flocking to the Supreme Court, there has been a visible fillip to the practise, attributable largely to the pioneering efforts of those like MNK.

My first interaction with MNK can be traced to my early years at the Bar, courtesy a chamber dinner where (as is the custom) distinguished alumni made their presence. I had not encountered MNK earlier, mainly because of the low profile he maintained. Even in the years since, I cannot recall a single television appearance of his or a quote to a publication. What I cannot forget was the manner in which he greeted me—warm and deeply affectionate, here was a man who wanted you to know that you meant something to him. Why a raw junior would evoke such a sentiment was a mystery, especially when that raw junior was me!

I wondered, as one would, whether this was just politeness on his part. Who would blame him for ignoring me the next day? To the contrary, not only did he wring my hand vigorously on the morrow (as well as remember my name), but he also gently urged me into a chair in the coffee shop where he plied me with some hot brew while exploring my past.

In those fleeting moments a lifetime ago, I realised why MNK was who he was—he was not flamboyant or larger than life. He was a compassionate soul who treated all others as equals, meriting respect, regardless of age or gown. It was in this that MNK transcended all the various complexes and charades at the Bar—he cared none for ego battles and luxury cars and badges of honour, choosing instead a path of spiritual learning, which finally brought him to Satya Sai Baba’s embrace. As Senior Advocate K.V. Viswanathan says—“he walked with kings but never lost the common touch”.

Later, as a co-trustee on the Supreme Court Lawyers’ Welfare Trust, all of us banked on MNK to give guidance on which were the deserving cases of advocates that required our assistance. While some of us discharged the simple task of signing cheques, it was MNK who, of his own volition, visited the bedsides of suffering advocates and held the hands of their family members. He listened with patience as others bemoaned the fate of a loved one and was swift to reach for his wallet. Those who remember earlier Bar functions would recall the slight figure of the late Mr Gupta on each occasion, his coat pockets swelling with pens of every hue. Once again, as he battled a debilitating disease, it was MNK who was a pillar of support till the end. There are countless such incidents which each member of the Bar would recount, but to those who were deprived of his munificence, this account attempts? to make modest amends.

I must hasten however to dispel the notion that MNK was soft or non-confrontational. For him, the institution was pre-eminent, and anyone who trifled with it would face his resistance, be it the Chief Justice of India (as the Sahara hearings evidenced) or a mere commoner. His rectitude and the high esteem with which the Judges regarded him ensured that he would regularly intervene when he felt the Bench was being harsh on a junior. Often he would rise from the third row to object to the manner in which a colleague was being treated, an attribute sorely absent in others of his ilk.

It is unfortunate that in his final years, his avowed spiritual path lent a saffron hue to how he was perceived. This is why he probably felt the need to point out in that last fateful speech that he was a devotee of all faiths and that he had even composed Bhajans on Allah and Christ.

I have deliberately avoided alluding to MNK’s prowess as an advocate, because it would be a great disservice to reduce an understanding of who he was to something as banal as his practise in court. His work outside the courtrooms undoubtedly outshone that of virtually everybody else within them, and it is in that space we find a yawning gap. As the Bard said — “When will we find another?”

Farewell, dear MNK—remember us to the angels with whom you share a table at the Great Coffee Shop in the sky.

_____

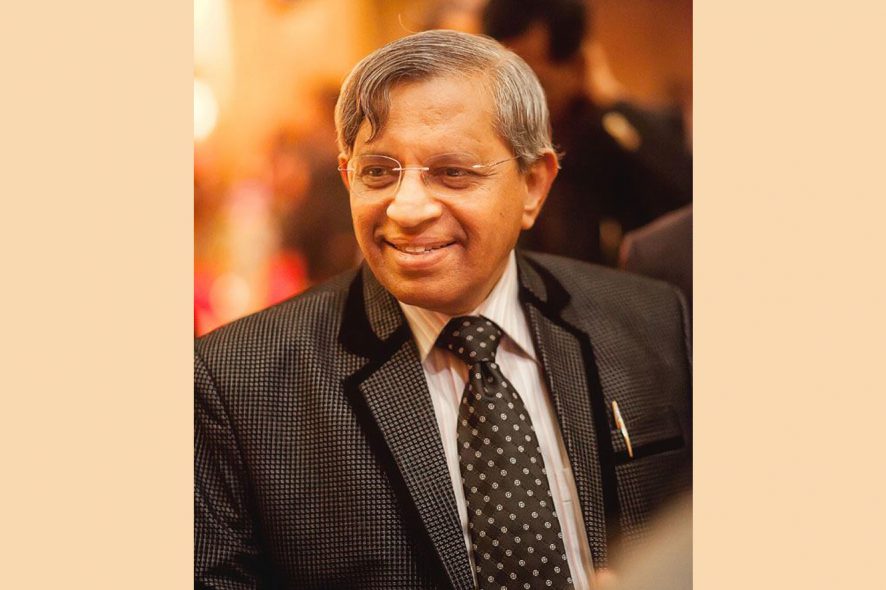

[Dr M.N. Krishnamani, Padam Shri, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India, Former President, SCBA, passed away on 15-2-2017. He was 68.]