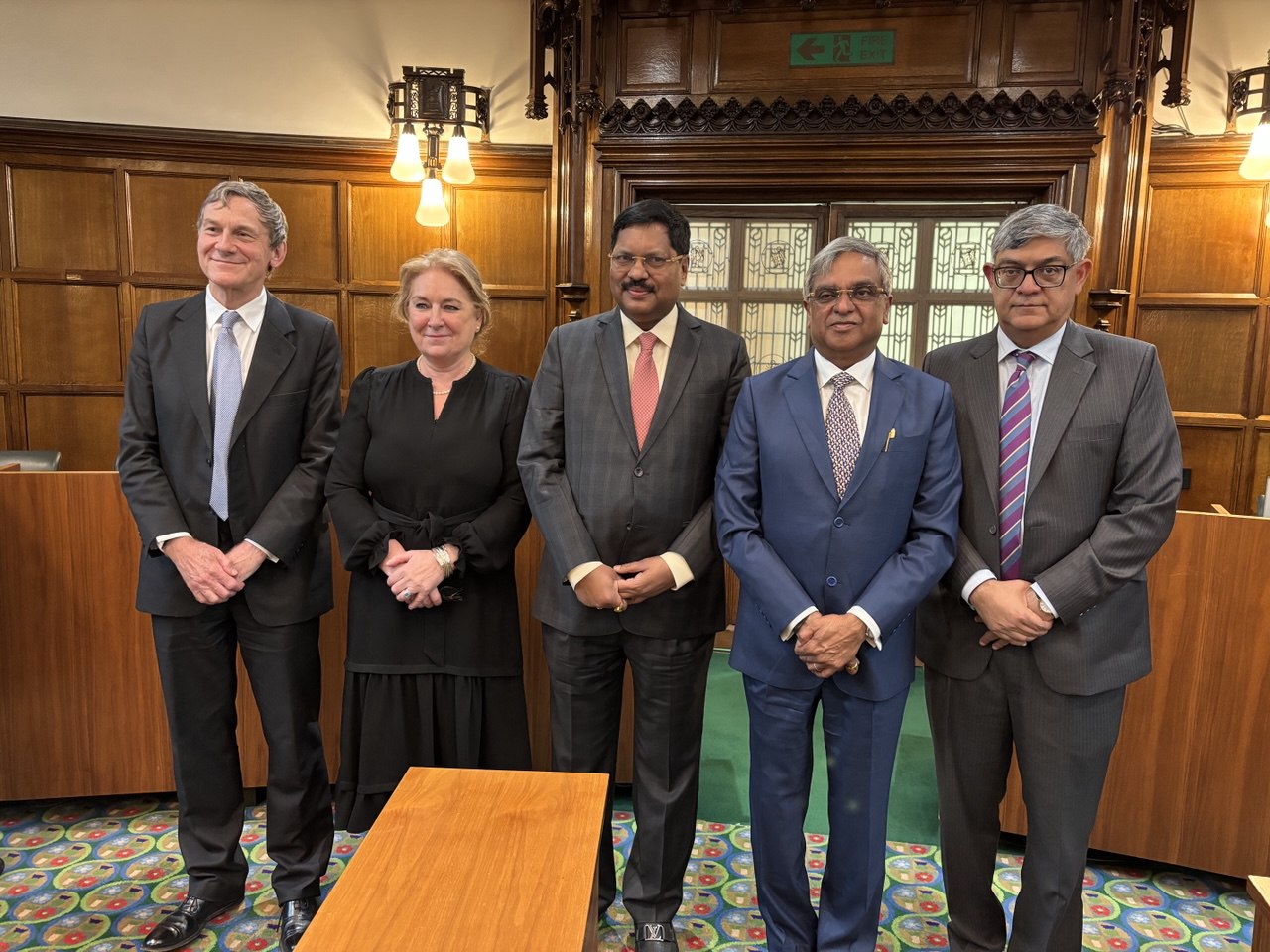

In an extraordinary gathering at the UK Supreme Court, leading jurists from India and the United Kingdom came together for a closed-door roundtable discussion on the pressing theme of “Maintaining Judicial Legitimacy and Public Confidence.” The session was hosted by Gourab Banerji, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India and featured the Chief Justice of India, B.R. Gavai, Lord Leggatt, UK Supreme Court, Justice Vikram Nath, Supreme Court of India, and Baroness Sue Carr, Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales.

The discussion explored complex issues of judicial independence, constitutional supremacy, live streaming of court proceedings, and the judiciary’s evolving role in an age of social media and growing public scrutiny.

Mr. Banerji opened the dialogue by highlighting the centrality of the Constitution in sustaining the rule of law and justice in democratic states. He acknowledged the increasing erosion of public confidence in the judiciary globally, amplified by social media and public commentary—often based on misinformation.

“The judiciary, by its independent nature, is not directly accountable to the electorate, and therefore, maintaining public confidence is not just a necessity, it is an obligation,” Banerji emphasised.

He pointed to how criticism of the judiciary has become less deferential and more vociferous, coming not only from litigants and counsel but also from the media and even elected officials.

In response to Mr. Banerji’s question on how the Indian judiciary navigates the tension between an elected majority and constitutional safeguards, Justice Gavai reaffirmed the primacy of the Constitution over all other branches of government.

He provided a detailed legal-historical overview—from Shankari Prasad Singh Deo v. Union of India, 1951 SCC 966 to Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 SCC 225—emphasising the basic structure doctrine and the limits of Parliament’s amending powers.

Both the Supreme Court and High Courts in India possess the power to declare legislation unconstitutional, even if passed by an absolute majority. But this power must be exercised judiciously, he noted.

He also briefly discussed the balance between constitutional fidelity with public will. He referenced landmark cases such as Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, (1997) 6 SCC 241, where the Supreme Court issued guidelines in the absence of legislative action, underlining that the judiciary acts not politically, but constitutionally.

Baroness Carr, Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales, reflected on the judiciary’s fundamental responsibility in upholding democratic principles, emphasising the delicate balance courts must maintain in a system without a written constitution:

Despite the fact that we don’t have a written constitution, our case law demonstrates that we respect boundaries, understand them well, and give appropriate deference to areas where the executive or Parliament is making primary decisions. Parliament is sovereign and can change the law, but our case law aligns with respecting those areas where it is not for us to interfere, she remarked.

She highlighted the greatest tension often arises when courts make cutting-edge decisions as experts, acknowledging the need for judicial restraint while recognizing the challenges posed by modern communication channels:

“In the changing times we live in, the judiciary faces unprecedented levels of inaccurate, disrespectful commentary, especially on social media… We must never jeopardize our independence, impartiality, and integrity.”

She stressed the importance of judicial communication evolving with societal changes but always within constitutional safeguards to protect judicial independence.

Lord Leggatt elaborated on the UK’s constitutional framework, underscoring legislative supremacy in the absence of a written constitution, and clarified common misunderstandings about the roles of Parliament and government:

“We don’t have a written constitution… The basic principle is legislative supremacy—Parliament can ultimately do what it likes. The closest judicial check is under the Human Rights Act, 1998 where the court can issue declarations of incompatibility, but it is up to Parliament whether to act on those”, he underscored.

He criticised misconceptions, especially in media, about courts blocking government actions, explaining:

He explained that the public elects members of Parliament who pass legislation, which government ministers must obey. Courts find unlawful government actions—not oppose government itself—and that is part of their job.

Regarding communication, Lord Leggatt described efforts to improve public understanding of judicial decisions:

We issue press summaries and sometimes short video summaries of judgments to encourage accurate reporting… We have a press department answering questions. Some courts, like Sweden’s Supreme Court, even give press conferences on judgments, which we have not yet done.

Justice Vikram Nath, reflecting on his experience as Chief Justice of Gujarat High Court, where he championed live streaming and transparency as essential for public trust:

He voiced that he is a strong supporter of live streaming and that the aggressions and misuse are minimal compared to the advantages it provides judges, lawyers, litigants, and the public.”

He shared how live streaming court proceedings opens the courtroom to the public, transforming justice from an “esoteric ritual” to a visible, accountable public act:

“Citizens watching from a village or a classroom see the same submissions and reasoning… This shared vantage point strengthens the idea that justice is performed on the people’s behalf.”

Justice Nath acknowledged concerns about social media misuse but argued that full recordings with context mitigate the risks of out-of-context clips:

“Newspapers have always published fragments without context. The answer is to provide full recordings so context is just a click away. Judges are experienced at separating substance from theatrics.”

On the negative aspect, he furthered that snippets circulating on social media and out of context comments is a genuine fear. He outlined safeguards for sensitive cases, such as delaying broadcasts or blurring identities, and underscored the importance of balancing transparency with protecting parties and case integrity.

Quoting Lord Denning, he emphasised the need for stability in principle with openness in method.

On the same note, Justice Gavai highlighted challenges in India regarding social media abuse and the lack of regulatory measures for judicial protection.

Taking the conversation ahead, Moderator Gourab Banerji raised the critical question of whether the judiciary should communicate beyond judgments to build public confidence.

Justice Baroness Carr noted that traditionally judges speak only through their judgments to maintain professionalism and avoid politicisation but acknowledged that changing times demand openness to new modes of public engagement:

“We can build on judicial websites, reports, public legal education, apps, and possibly media-trained judges who explain court processes in neutral terms without commenting on individual cases.”

However, she expressed skepticism about certain claims on transparency, emphasising the importance of cautious, gradual implementation of live-streaming and public access initiatives in courts. She highlighted that all hearings are currently available for real-time viewing or later online access via official government websites, which has been positively received by judges overall. She acknowledged the significant challenges related to security and threats, which require robust safeguards before expanding transparency. She stressed the need for broader access to justice beyond visual transparency, advocating for improved public and media access to legal documents, accurate hearing notifications, and understandable court materials.

Lord Leggatt shared reflections from the UK judicial experience, noting that televised court clips have yet to become popular on social media, saying, “I think they’re probably too dull for that.” He recounted a personal anecdote: “At the end of the time I’ve never been recognised by a member of the public as a judge. But somebody came up to me in a supermarket and asked whether I was the person he’d seen on the Supreme Court live stream.”

On judgement writing, Lord Leggatt observed the impact of technology with a mix of praise and critique. He commented, “One of my bugbears about judgements is long quotations of previous judgements. There is nothing more boring than reading a judgement to come across a large block of text which the judge has cut and pasted.” He also criticised overly lengthy recitations of arguments.

Justice Gavai highlighted initiatives in India to improve accessibility through language diversity, noting, We are now using technological tools to translate our judgements into various Indian languages… because India is a land of diverse languages.

Lord Leggatt concluded by emphasising the importance of clarity and communication in judicial writing.

Conclusively, the discussion revealed a shared commitment across jurisdictions to uphold judicial independence and democratic principles while recognising the evolving role of communication in fostering public trust. Balancing transparency, protection of judicial integrity, and adapting to technological change remains a core challenge.