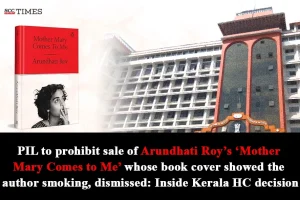

Kerala High Court: The petitioner filed a public interest litigation seeking to prohibit the sale, circulation, and display of Arundhati Roy’s book – ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’, as its cover depicted the author smoking a cigarette, which was alleged to be in contravention of the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Act, 2003 (‘Act of 2003’). The Division Bench of Nitin Jamdar, CJ.*, and Basant Balaji, J., dismissed the writ petition and held that the petitioner had invoked the extraordinary jurisdiction of the Court under the guise of public interest, despite there being an alternative remedy of approaching the Steering Committee available.

Background:

Arundhati Roy’s book titled ‘Mother Mary Comes to Me’, published by Penguin House, was released on 02-09-2025. The petitioner, a practicing advocate, filed a PIL stating that her image on the book’s cover, smoking a cigarette, was in contravention of the provisions of the Act of 2003. He sought a direction to the Union of India, Press Council of India, and State of Kerala, to prohibit the sale, circulation, and display of the book, and to direct Penguin House to withdraw all copies of the book. The petitioner urged that because of violation of Section 5 of the Act of 2003, Sections 7 and 8 of the Act were triggered, and the Official Respondents were obliged to take appropriate action against Arundhati Roy and Penguin House, in respect of the book in question.

The Central Government, under Section 25 of the Act of 2003 and Rule 4 of the Cigarettes and Other Tobacco Products (Prohibition of Advertisement and Regulation of Trade and Commerce, Production, Supply and Distribution) Rules, 2004 (‘Rules of 2004’), had constituted the Steering Committee to examine the alleged violations under Section 5 of the Act of 2003. The Steering Committee was empowered to take cognizance suo motu or examine specific violations under Section 5 of the Act of 2003, including cases relating to indirect advertising and promotion, and to pass appropriate orders.

The counsel for Union of India submitted that the Steering Committee was the competent authority to examine the allegations of violations. Any member of the public could submit a complaint, including through the online portal, and the Steering Committee was required to afford a hearing to the person against whom the complaint was made before passing any order. The counsel contended that the petitioner had rushed to the Court without first approaching the designated expert authority.

Penguin House submitted that the petitioner did not disclose the presence of a disclaimer in the book, which stated that the depiction was not intended to promote smoking, and he wrongly stated in his petition that depictions of smoking in films, television, and media were required to carry statutory health warnings. The petitioner had not complied with Rule 146AD of the Rules of the High Court of Kerala, 1971, which mandated disclosure as to whether he had approached the competent authority for redressal of the grievance before invoking the writ jurisdiction of the Court. Penguin House reiterated that Section 5 focused solely on the prohibition of advertisements of cigarettes and that images or depictions such as those on a book cover were not covered under the Act of 2003, yet it had volunteered to place a disclaimer in the book. It was also submitted that the book cover was an integral and inseparable part of the book, and that the petitioner could not infringe the fundamental rights of Arundhati Roy and Penguin House under Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

Analysis and Decision:

The Court noted that the petitioner filed the petition with a photo of the book cover and a copy of the Act of 2003 as the only annexures, without making any reference to the Rules framed under the Act and other details compiled in the Guidelines for Law Enforcers for Effective Implementation of Tobacco Control Laws, 2024, published by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

The Court asked the petitioner as to why he did not disclose the disclaimer placed in the book, to which he answered that he had not examined the book before filing the petition, which the Court found unsatisfactory and opined that greater diligence and responsibility was expected, particularly in a petition filed by an advocate raising legal issues.

The Court noted that the Steering Committee was made up of senior officers and domain experts from different fields, chaired by the Secretary, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Its members included a nominated Member of Parliament, Director General of Health Services, Joint Secretaries from Ministries of Information & Broadcasting and Law & Justice, representatives of the Advertising Standards Council of India and the Press Council of India, a senior preventive oncology professional, a Non-Governmental Organisation, Consumer Online Foundation representative, and the Joint Secretary in-charge of Tobacco Control. This diverse composition ensured a holistic and expert consideration of alleged violations of Section 5 of the 2003 Act.

The Court observed that the exercise of writ jurisdiction by the petitioner despite the existence of an alternative remedy was wholly misguided. He did not approach the Court for a personal cause but purported to raise an issue for the benefit of the public. The Court opined that the petitioner had, for no reasons, raised doubts as to the credibility of the Steering Committee and had not made even a minimal effort to ascertain the true facts or the correct legal position before invoking the jurisdiction of the Court.

The Court referred to Dattaraj Nathuji Thaware v. State of Maharashtra, (2005) 1 SCC 590, wherein it was observed that “public interest litigation was a weapon which had to be used with great care and circumspection and the judiciary had to be extremely careful to see that behind the beautiful veil of public interest, an ugly private malice, vested interest and/or publicity-seeking was not lurking”.

The Court observed that where there was any infringement of Section 5 of the Act of 2003, such matters were to be decided by the Steering Committee, after affording an opportunity of hearing to the parties. The Court noted that despite making the petitioner aware, he did not take up the issue before the competent expert statutory authority and filed the petition without examining the relevant legal position, and without verifying the necessary material, including the presence of a disclaimer on the book, rather, he invoked the extraordinary jurisdiction of the Court under the guise of public interest.

Consequently, while dismissing the writ petition, the Court emphasised that the Courts must ensure that public interest litigation was not misused as a vehicle for self-publicity or for engaging in personal slanders.

[Rajasimhan v. Union of India, 2025 SCC OnLine Ker 10315, decided on 13-10-2025]

*Judgment authored by: Chief Justice Nitin Jamdar

Advocates who appeared in this case:

For the Petitioner: N. Gopakumaran Nair (Senior), S. Prasanth, Helen P.A., Athul Roy, Renuka Venu, Indrajith Dileep, Amala Anna Thottupuram, Advocates.

For the Respondents: Krishna S., CGC, Anil Sebastian Pulickel, Santhosh Mathew (Sr.), Arun Thomas, Veena Raveendran, Karthika Maria, Shinto Mathew Abraham, Leah Rachel Ninan, Mathew Nevin Thomas, Karthik Rajagopal, Kurian Antony Mathew, Aparnna S., Noel Ninan Ninan, Adeen Nazar, Arun Joseph Mathew, Advocates.