The acceptance of olfactory mark undeniably marks a watershed moment in the evolution of trade mark jurisprudence in India.

Introduction

The Trade Marks Registry on 21 November 2025 accepted and directed to advertise the Trade Mark Application Bearing No. 5860303 for “Floral Fragrance/Smell Reminiscent of Roses as Applied to Tyres” in Class 12 on a “proposed to be used basis” in accordance with the provisions of Section 20, Trade Marks Act, 1999 as an “olfactory mark”.

This is an unprecedented development in the field of trade marks. Never before has an olfactory mark been accepted by the Trade Marks Registry. It is not that the application did not face its own set of novel challenges along the way, but after analysing the Order of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (CGPDT)1 granting acceptance to the said application, it could be said that more questions remained unanswered than were answered.

This article undertakes a critical analysis of the Trade Marks Registry’s unprecedented decision, examining two fundamental issues: First, whether the graphical representation provided by the applicant truly satisfies the statutory mandate of clarity and precision as envisioned in Section 2(1)(zb), Trade Marks Act, 1999, and second, whether the applicant’s reliance on international precedent accurately reflects the legal frameworks of those jurisdictions.

Ambiguity of the graphical representation

The CGPDT in his Order accepting the olfactory mark, stated that the said mark satisfied the criteria laid down for registration under the Trade Marks Act, 1999, “as it is clear, precise, self-contained, intelligible, objective and is represented graphically”.

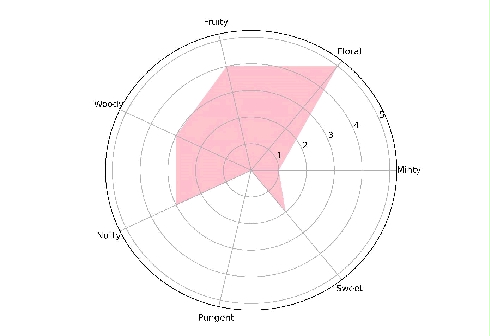

The graphical representation is mentioned below:

This graphical representation was also accompanied by a description, which states:

A complex mixture of volatile organic compounds released by the petals interact with our olfactory receptors, creating a rose-like smell. Using the technology developed at IIIT Allahabad, this rose-like smell is graphically presented above as a vector in the 7-dimensional space wherein each dimension is defined as one of the 7 fundamental smells, namely, floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet and minty.

Although no judicial decision of any Court in India could be located that has elaborated on the purpose of the requirement of graphical representation of the mark for it to be a trade mark, it could be intelligibly presumed that this prerequisite is present in Section 2(1)(zb) so as to enable people to determine the said mark with clarity and precision. The same is reinforced by the analysis given by the CGPDT in Para 34 of his Order which states:

The graphical representation is detailed and clearly defines and distinguishes, with a scientific temperament the presence of the constituent elements, including their scale or weightage in the overall composition. The graphical representation would enable the competent authorities and the public to determine the precise subject-matter of protection. I am therefore of the considered opinion that the above representation sufficiently captures the metes and bounds of the smell in question and complies with the mandatory requirements of Section 2(1)(zb) of the Act.

Now, in the present application for the registration of the olfactory mark, the graphical representation of the mark manifestly fails the test of precision.

The CGPDT Order states that the graphical representation is a vector in the 7-dimensioal space wherein each dimension is defined as one of the 7 fundamentals smells, namely, floral, fruity, nutty, pungent, sweet, and minty. The methodology employed to develop this graphical representation was based upon supervised machine learning, with additional processing and analysis for identifying the top 5 contributing compounds, and an algebraic average of vectors.

Keeping in mind that the objective of graphical representation of the mark is to add precision and clarity, if one views the aforementioned graphical representation, one would find it extremely difficult if not impossible to come up with “rose-like smell” as his answer. Now, let us view this graphical representation in light of the description provided with it. The description explicitly mentions a “rose-like smell” leaving little to the imagination of the person reading it. The graphical representation must be accompanied by a description to give an idea that the smell depicted is a “rose-like smell” but on the other hand the description standalone paints a clear picture of the olfactory mark leaving the graphical representation redundant or rather inconsequential. This begs the question that did the graphical representation even fulfil the criteria it is mandated by the statute or was this treated like a mere inconsequential procedural step.

Misinterpretation of international frameworks

The applicant in their submissions mentioned the fact that smell marks have been considered as capable of registration as trade marks in multiple jurisdictions across the world including in Australia, Costa Rica, European Union, United Kingdom and the United States of America. The applicant also stated that the trade mark laws of Australia and United Kingdom specifically require a trade mark to be graphically represented. Let us dissect this claim to verify its veracity. The applicant’s claim is technically grounded but contextually distorted. While Section 40, Trade Marks Act, 1995 (AU) indeed mandates that an application be rejected if the mark cannot be “represented graphically”, the Australian Intellectual Property Office’s interpretation of this requirement differs vastly from the approach taken in the present case. In Australian practice, a concise written description (for example, “the scent of cinnamon”) is routinely accepted as satisfying the graphical representation requirement. Therefore, citing the Australian statutory mandate to justify the use of a cryptic 7-dimensional vector graph creates a false equivalence; the Australian regime uses graphical representation to ensure simplicity and clarity, whereas the applicant has used it to introduce scientific complexity that obscures the mark’s identity. Moreover, Section 17, Trade Marks Act, 1995 (AU) states:

17. What is a trade mark?.— A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

Section 6, Trade Marks Act, 1995 (AU) includes the definition of sign, which states:

6. Definitions.— sign includes the following or any combination of the following, namely, any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent.

When these two definitions are read conjointly, it becomes amply clear that as per the Trade Marks Act, 1995 in Australia, a “scent” is a sign that could be a “trade mark”.

In the case of UK, Section 1(1)(a), Trade Marks Act, 1994 (GB) states that:

1. Trade marks.— “trade mark” means any sign which is capable

(a) of being represented in the register in a manner which enables the registrar and other competent authorities and the public to determine the clear and precise subject matter of the protection afforded to the proprietor.

Nowhere in this definition has the term “graphically represented” has been employed as is claimed by the applicant to substantiate their position. So, the claim by the applicant that the trade mark laws of Australia and United Kingdom specifically require a trade mark to be graphically represented lacks statutory basis.

Moreover, if the earlier submission of the applicant, that smell marks have been considered as capable of registration as trade marks in multiple jurisdictions across the world including in Australia, Costa Rica, European Union, United Kingdom, and the United States of America, were to be analysed, one would find out that the trade mark laws of none of these countries impose a condition of “graphical representation” on a mark for it to registered as a trade mark. There might be other restrictions which could prevent the registration of smell marks within these jurisdictions but the restriction of “graphical representation” certainly is not one of them.

Conclusion

The acceptance of this olfactory mark undeniably marks a watershed moment in the evolution of trade mark jurisprudence in India. However, the pioneering nature of this decision does not insulate it from critical scrutiny. The CGPDT’s Order, rests on foundations that warrant closer examination.

The “graphical representation” approved in this case exposes a fundamental lacuna within Section 2(1)(zb), Trade Marks Act, 1999. The representation can hardly be said to enable the “public” to determine the precise subject-matter of protection, unless one presumes the average consumer possesses expertise in olfactory science and vector mathematics. The reliance on an accompanying textual description to convey that the mark represents a “rose-like smell” effectively reduces the graphical representation to a mere formality rather than a functional requirement of the statute.

Furthermore, the applicant’s comparative law submissions present an inaccurate picture of other trade mark regimes. Neither Australia nor the United Kingdom mandates “graphical representation” as a precondition for a trade mark registration; rather, both jurisdictions have moved toward more flexible representation requirements. This mischaracterisation should have prompted greater circumspection on the part of the Registry.

While the acceptance of this olfactory mark may be considered a progressive step towards embracing non-conventional marks, the manner in which it has been granted risks setting a precedent that prioritises novelty over legal rigour.

*Advocate, Delhi. Author can be reached at: advocate.shubhang@gmail.com.

1. Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Notification No. TMR/DEL/SCH/2025/16 (Notified on 21-11-2025).